Israel has fought numerous wars with Arab states since its founding in 1948. Although peace treaties with Egypt (1979) and Jordan (1994) have endured, Israel remains technically in a state of enmity with Syria and Lebanon. It lacks official diplomatic relations with most Arab and Muslim-majority states barring Turkey and, recently under the Abraham Accords, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco. Political conflict has been accompanied by economic conflict—for example, the Arab state boycott of Israeli products.[1]

Historically, Israel has pushed for recognition from and “normalization” of relations with the Arab world, while Arab states have sought Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories and rights for Palestinians in accordance with international law, such as UN Resolution 242. However, peace agreements, starting with the Egypt-Israeli agreement, have tended to sideline international law and Palestinian sovereignty in favor of normalization efforts.[2] Although Egypt was initially shunned for its recognition of Israel, the 1991 Madrid Conference and later the Oslo process opened the door for bilateral meetings and economic summits between Israel and the Arab world.[3] In late 1994, for instance, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) officially relaxed their enforcement of the Arab League boycott,[4] and U.S.-promised economic ‘peace dividends’ also induced Morocco and Tunisia to exchange liaison offices with Israel and initiate direct economic relations.[5] However, the onset of the Second Intifada in 2000 challenged and reversed this growing shift toward normalization.

The Arab Peace Initiative

Under the leadership of Saudi Arabia, in 2002, the Arab League offered full normalization of relations with Israel in exchange for Israeli withdrawal from the territories occupied in 1967, the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state, and the settlement of the Palestinian refugee issue; those were reaffirmed in 2005, but not officially acknowledged by Israel.[6] The Arab Peace Initiative (API) signified the first significant shift away from the Arab states’ “three Nos” (no to peace with Israel, no to recognition of Israel, and no to negotiations with Israel) of 1967 to “three "yeses": yes to peace with Israel, yes to recognition of Israel, and yes to negotiations with Israel.”[7] However, between poor timing and lack of acknowledgment by Israel and the U.S., it did not lead to any diplomatic breakthroughs.

In 2020 several Arab states announced U.S.-brokered full normalization agreements with Israel, absent any explicit compromises on Israel’s side vis-à-vis the Palestinians, a significant shift from traditionally held positions. On 13 August 2020, Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, announced an agreement with then-U.S. President Trump and then-Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu “to stop further Israeli annexation of Palestinian territories” and “to cooperation and setting a roadmap towards establishing a bilateral relationship.”[8] A joint statement of the U.S., Bahrain, and Israel was released on September 11, announcing the “establishment of full diplomatic relations” between Bahrain and Israel.[9] The two announcements became official on September 15 during the Abraham Accords signing ceremony at the White House. On October 23, Sudan and Israel announced the normalization of relations[10], only days after the U.S. officially removed Sudan from the list of states sponsoring terrorism; they formally signed the Abraham Accords on 6 January 2021.[11] Morocco joined the Abraham Accords on December 10, 2020, as part of a quid pro quo. It established full diplomatic relations with Israel in exchange for U.S. recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over disputed Western Sahara. Subsequent to signing the accords, Arab states repealed the remaining boycotts on Israel, contributing further to normalization. However, Israel did not make any reciprocal moves regarding territorial withdrawal from occupied territories, recognition of Palestinian rights, or addressing the issue of Palestinian refugees.[12]

While several of these states already had informal security, intelligence, and trade relations with Israel and, except for Sudan, were never at war with Israel, these agreements represented a significant shift in historical Arab-Israeli relations and thus required some discursive justification. Here, we examine how the Abraham Accords were framed in the Israeli press and explore how the Accords have impacted Israel’s economic and security situation.

What Kind of Peace Accord?

The 2020 Abraham Accords garnered two main reactions. One camp heralded these agreements as an achievement of peace, while the other condemned them as mere business agreements or a betrayal of the Palestinian cause. These reactions reflect contending views on peace held by Israel and the Palestinians, with the former seeking recognition and security (normalization) and the latter seeking resolution of conflict issues and adherence to international law. These contending reactions also correspond to divergent concepts of and approaches to “peace” in the literature. Popularized by Johan Galtung, negative peace denotes a narrow conception of peace limited to the absence of war, violence, or direct conflict, similar to a “cold” peace.[13] In contrast, positive peace signifies the absence of structural and cultural violence and includes justice, rights, freedom, and “the integration of human society.”[14] In the following sections, we explore narratives surrounding the agreements and what type(s) of peace are advanced in Israeli media narratives.

Method

This article uses quantitative and qualitative data to explore how the Abraham Accords were portrayed in the Israeli media. It first draws on quantitative data obtained from Google’s Global Database of Events, Language and Tone (GDELT) project using Tableau software package to generate graphs that capture the events and words frequently mentioned in Israeli news coverage of the Arab signatories to the Abraham Accords in the weeks when the Accords were announced for each of the respective Arab states. The GDELT Project is an open news index that monitors, collects, and translates global news from 1979 onward. GDELT 2.0 codes the data along three themes: actor attributes (we use Israel as ACTOR 1 and the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco separately as ACTOR 2), event action attributes (e.g., type of event, number of mentions, we look at terms such as economic and diplomatic cooperation), and event geography (latitude and longitude).

We also captured the levels of economic exchange between Israel and the Arab signatories to the Abraham Accords to examine the extent to which the Accords translate to material cooperation.

To add greater context and nuance to the quantitative data, we qualitatively analyzed a sample of Israeli news articles from the same time frames from four Israeli English news sources: the Jerusalem Post, Ynet, Israel Hayom, and 972 Magazine. These were all freely accessible online, capturing a wide range of Israeli perspectives. One article was selected from each publication for each of these date ranges, except there was no 972 Magazine coverage of the Moroccan deal. The articles were thematically coded in terms of how the agreements impacted Israel in economy, security, and peace. Given the controversy surrounding the normalization agreements, we also coded any references to Palestinian concerns.

Trade Data for The West and Abraham Accords Signatories

Using available online databases and institutional reports, we investigated how the Abraham Accords impacted the Israeli economy and security situation. Limited data exists for economic relations between Israel and the Gulf states before 2020 due to the unofficial nature of these interactions. Further, as there has been no armed conflict between Israel and the Abraham Accords signatories, there are no conflict deaths to report. One can look at conflict data related to Israel/Palestine as a proxy for a more direct conflict/security impact on Israel. Table 1 shows human fatalities in Israel and the Palestinian Territories over the past five years. The data for 2021 and 2022 indicate that the Abraham Accords had no effect in reducing fatalities; as Palestinians were excluded from the agreements, this is unsurprising.

Table 1: Human fatalities in Palestine and Israel between 2017 and 2022

|

Years

|

# of Palestinian deaths

|

# of Israeli deaths

|

|

2017

|

77

|

17

|

|

2018

|

300

|

13

|

|

2019

|

138

|

12

|

|

2020

|

30

|

3

|

|

2021

|

349

|

11

|

|

2022

|

139

|

13

|

Source: Data on casualties. https://www.ochaopt.org/data/casualties#

Note: Data for 2022 are partial.

Trade is a second key factor emphasized in the agreements. In addition to trade with the states signing the accords, the agreements could also affect Israel’s trade with the West, as such states have used trade as a political leverage point. After the Oslo Accords, for example, Israel benefited from a so-called “peace dividend.” Table 2 shows available trade statistics for the past five years. In 2021 Israeli trade with the EU, the U.S., and the U.K. was valued at US$45, 24, and 5 billion, respectively. In comparison, one year after the Accords, total Israeli bilateral trade with the UAE was roughly US$1 billion. While low compared to Israeli trade with its Western partners, it nevertheless marks a significant increase from nearly US$ 200 million in 2020. Further, partial trade data for 2022 shows an increase of up to US$1.407 billion,[15] and these numbers will likely increase further due to the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement signed by Israel and the UAE in 2022.[16] Trade with Morocco was also comparatively low, at US$ 42 million in 2021, but this is double 2020’s figures.[17] While Bahrain has the least trade with Israel, with roughly US$6.5 – 7.5 million in 2021, it is higher than Sudan, which thus far lacks any official trade with Israel.[18] This is not surprising given that the economic disparities between Sudan and the other three states.

Trade is a second key factor emphasized in the agreements. In addition to trade with the states signing the accords, the agreements could also affect Israel’s trade with the West, as such states have used trade as a political leverage point.

Table 2: Bilateral trade between Israel and the EU, the US, the UK, and the four Abraham Accords signatories between 2019 and 2022 (in millions of US$)

|

|

EU

|

U.S.

|

U.K.

|

UAE

|

Bahrain

|

Sudan

|

Morocco

|

|

2019

|

37,093.60

|

17,652.30

|

8,027.30

|

11.2

|

|

|

13.7

|

|

2020

|

35,090.80

|

21,181.80

|

6,681.40

|

188.9

|

|

|

22.6

|

|

2021

|

45,054.20

|

24,487.70

|

5,377.20

|

1,155

|

6.5

|

|

41.6

|

|

2022

|

|

|

|

1,407[19]

|

|

|

24.3[20]

|

Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2022/fr_trade12_2021/td1.pdf

Note: Data for 2022 are partial.

Quantitative Findings

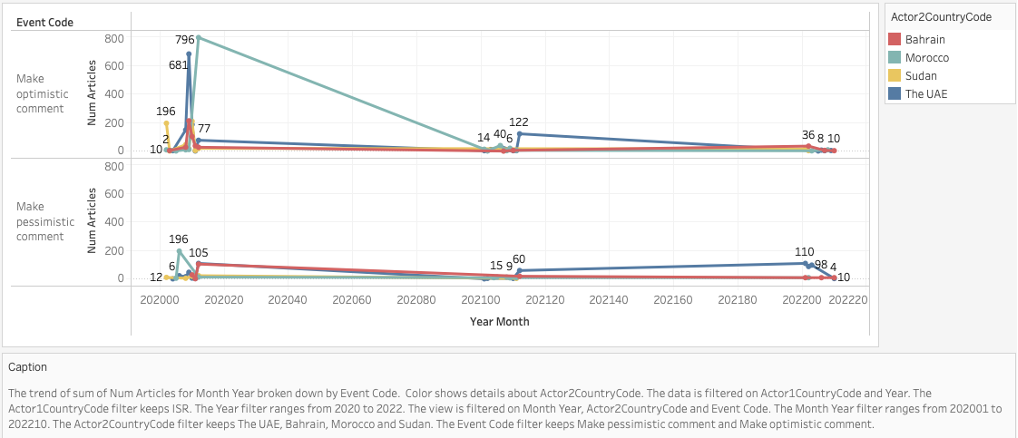

Figure 1 shows the extent to which content mentioned within Israeli newspapers about the four Accords signatories was optimistic or pessimistic. During the entire period between 2020 and 2022, pessimistic comments remained below 200 articles, whereas optimistic comments reached close to 800 at the peak. As expected, optimistic comments spiked during the first weeks following the announcement of the Accords, with 681 optimistic comments about the UAE and 796 about Morocco.

Figure 1: Optimistic and negative comments about Abraham Accords signatories in Israel media between 2020 and 2022

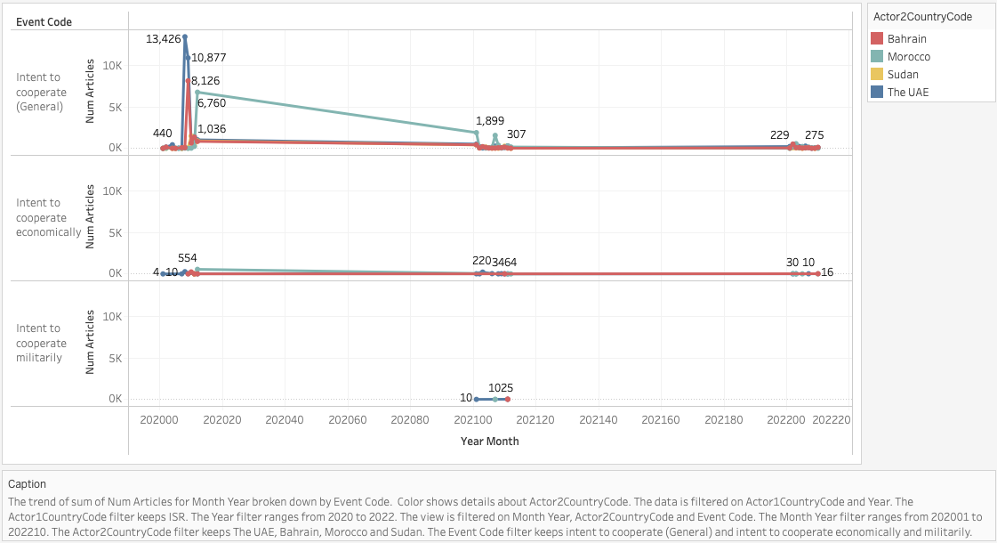

Figure 2 captures the extent to which Israeli newspapers mentioned intent to cooperate in general and to cooperate economically and militarily. Numbers spiked in the first weeks following the announcement and signing of the Accords, with the UAE (13,426 articles) and Morocco (8,126 articles) receiving the highest coverage. However, there was relatively little mention of economic and military cooperation specifically.

Figure 2: Mentions of intent for material cooperation with Abraham Accords signatories in Israel media between 2020 and 2022

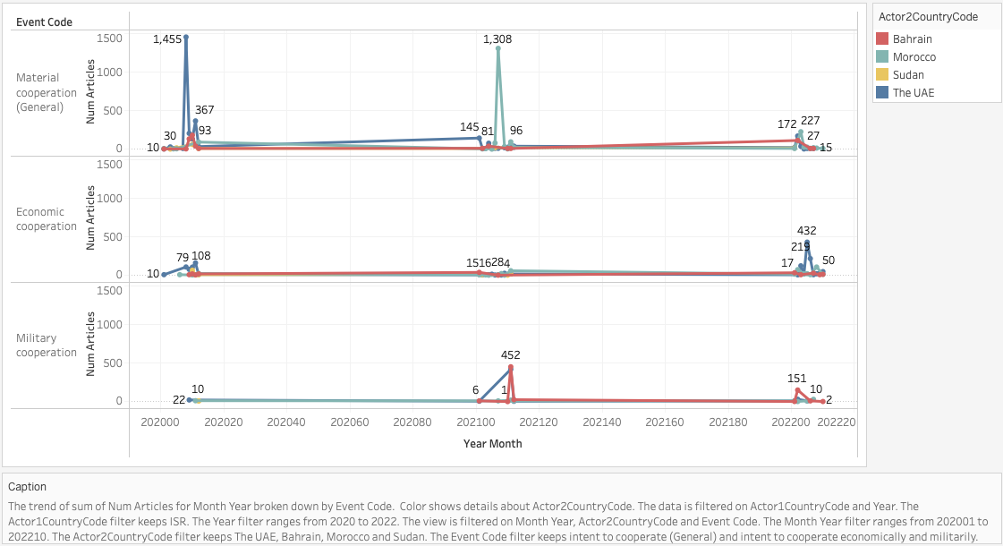

Figure 3 goes beyond intent to capture engaging in material cooperation between 2020 and 2022. The first query captures general material cooperation, while the second and third queries explore economic and military cooperation. The UAE received the highest media coverage for material cooperation (1,455 articles) in the first few weeks following the Accords. The rest of the signatories received relatively low media coverage throughout 2020 and 2022. The most notable exception is Morocco in July 2021, which saw 1308 Israeli media articles mentioning material economic cooperation. On July 25, 2021, Morocco and Israel officially launched nonstop commercial flights between the two countries, materializing the goals of increasing tourism, trade, and economic cooperation outlined in the Abraham Accords.[21] Overall, actual engagement in economic and military cooperation was low. Notable spikes correlate with the 31 May 2022, signing of the Israel-UAE free trade agreement, Morocco’s first defense agreement with Israel on November 24, and the UAE’s participation in a naval war drill with Israel, the U.S., and Bahrain.

Figure 3: Mentions of engaging in material cooperation with Abraham Accords signatories in Israel media between 2020 and 2022

Qualitative Findings

In contrast to the quantitative findings that found more mentions of general cooperation, the qualitative analysis indicates that economics and security were primary considerations regarding Israel’s justification of the Abraham Accords to domestic audiences. Further, in contrast to the quantitative findings which show spikes for events primarily related to the UAE and Morocco, the qualitative sample provides more coverage of the UAE and Bahrain; there were fewer, shorter, and less comprehensive articles related to the agreements with Sudan and Morocco. For example, while the articles covering the UAE and Bahraini deals had author bylines and sometimes several lead authors, the pieces on Sudan and Morocco were sometimes simply attributed to “Staff” or were done in conjunction with news wires like Reuters. While this may have to do with the novelty of the agreements in the first months, further research should be done regarding the difference in coverage. For example, it may have to do with the difference in wealth between the countries, geographic differences, or factors related to the number of Moroccans and Sudanese living in Israel and associated domestic dynamics therein.

In contrast to the quantitative findings that found more mentions of general cooperation, the qualitative analysis indicates that economics and security were primary considerations regarding Israel’s justification of the Abraham Accords to domestic audiences.

Eleven of the 15 articles reviewed here (four articles for each of the three main newspapers and three for 972 Magazine) referred to economic benefits from the Abraham Accords. For example, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu suggested that signing the agreement with the UAE reflected his commitment “to pull Israel out of the world recession.”[22] Statements about the signing emphasized the potential for regional transformation, economic growth, technological innovation, and the launching of joint projects.[23] Some, such as the 972 Magazine’s Kattan, criticized the economic focus, suggesting that the deals conflated peace and prosperity “as if they were a single term.”[24] Coverage of the agreement with Sudan differed in focus, noting Israel’s provision of debt relief, aid, and investment in Sudan[25]and support for the government against Sudanese protesting financial crisis. Commentary surrounding the Moroccan agreement stresses economic connections in the tourist sector, given the number of Israelis of Moroccan descent and Morocco serving as a “gateway to Africa” for Israeli investors.[26] Most of the articles, however, did not discuss peace in the context of economics, but simply emphasized the economic benefits of the agreements, largely due to the opening of trade relations with advanced economies that were previous off limits (at least officially).

Twelve of the 15 articles reviewed discuss security in some way. Eichner noted that “the agreements won’t end active wars but will rather formalize the normalization of Israel’s already warming relations with the two [Gulf] countries.”[27]Regarding the agreements with the UAE and Bahrain, the emphasis is on the historically evolving cooperation noting that it has accelerated particularly with the rise in the Iranian threat.[28] While there is a thread of concern expressed in the articles regarding a possible loss of Israel’s qualitative military edge if the U.S. sells F-35 fighter jets to the UAE; overall, the emphasis is on the strategic partnership of these countries against Iran.[29] The one exception to the Iran-centered focus is the narrative around Sudan, where the narrative of anti-terrorism is more prominent. For example, Sudan designated Hezbollah as a terrorist organization, and the US removed Sudan from the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism.[30] Yet even in the coverage of the Sudan agreement there is mention of Sudan’s shift from Iranian to Saudi patronage in recent years[31]; the same anti-Iran focus holds in discussions of Morocco and their distrust of Iran due to Iran’s funding of the Polisario Front in Western Sahara.[32] Thus, the direction of the peace accords as presented to the Israeli public (at least in the English language version of its press) is in alignment with the narrative of Iran as the primary strategic threat facing Israel in the past years[33]. The articles note—and the data above support—that there has been no security threat to Israel from these Arab states in recent decades. This security-focused narrative aligns with the discourse of negative peace, in which ‘peace’ is equated with the absence of war rather than a set of positive set of conditions.

While the overwhelming emphasis of the sampled news articles was on the economic and security impact of the Abraham Accords, some noted benefits for Bahraini Jews and potential benefits for Sudanese refugees in Israel, although some raised concerns regarding possible repatriation to the Sudan.[34] Any repatriation without agreement by the refugees would violate international law and threaten human rights, thereby the antithesis of positive peace. Overall, however, the articles gave minimal discussion to concepts related to positive or warm peace in terms of positive and mutual understanding between peoples. Instead, the focus was on government elites and formal security and economic arrangements. While discussion of Palestinian statehood and Palestinian refugees was limited in the articles reviewed, a few pieces did contrast the successful negotiation of the Abraham Accords with the lack of progress on the Palestinian front.[35] Several correspondents acknowledged that Palestinians felt “stab[bed] in the back by fellow Arabs”[36] while others noted that the Gulf regimes were not allies of the Palestinians to begin with.[37] In an effort perhaps to quell criticism from their own populaces, Gulf leaders stated that their efforts helped put a stop to annexation of Palestinian territories by Israel and/or lay the groundwork for a lasting peace.[38] Overall, “peace” was not the main focus of the articles reviewed; the Abraham Accords were instead portrayed as a boon for Israel’s economy and security.

Conclusion

This preliminary study of the discourses surrounding the Abraham Accords suggests the agreements were, from the Israeli perspective, primarily about security and economic interests rather than cooperation more generally, although the data suggest more discussion of intent to cooperate rather than actual engagement in economic or security cooperation. While it is difficult to measure the economic impact due to the lack of records prior to 2020, Israel has had a positive economic benefit. However, it still pales compared to Israel’s trade with Western partners. Yet, the signing of trade deals with the UAE, Bahrain, and Morocco in 2022 means the economic impact is only beginning to show. Further, the qualitative findings suggest that the Israeli security narrative focuses on having allies against Iran, perceived as a collective threat to all involved parties, rather than any prior threat from these Arab states (or even Palestinians).

This project raises several questions for further study. First, it is worth examining other narratives about the agreements in the Israeli public sphere, including in Hebrew language papers, popular social media outlets, and military statements. Further, digging deeper into the differences in the narratives surrounding the Gulf states and the African countries would be helpful. This could reflect economic bias, or it could reflect racism or prejudices that have been documented elsewhere. Finally, the general lack of discussion of the Palestinians indicates the disconnect between the inter-state and intra-state dimensions of the Israeli-Arab conflict and Israel’s occupation of Palestine.

[1] Preston L. Greene Jr, "The Arab Economic Boycott of Israel: The International Law Perspective," Vand. J. Transnat'l L. 11 (1978): 77.; Amber Jameel Kalyal, "Israel and the Arab Boycott." Strategic Studies 21, no. 1 (2001): p. 167-193.;

[2] Marie-Christine Aulas, "The Normalization of Egyptian-Israeli Relations." Arab Studies Quarterly (1983): p. 220-236.

[3] Edward W. Said, “The end of the peace process: Oslo and after,” Vintage, 2007.

[4] Chaim Fershtman and Neil Gandal, "The effect of the Arab boycott on Israel: The automobile market," The Rand Journal of Economics (1998): p. 193-214.

[5] Kalyal 2001; Eliyahu Kanovsky, "Has the Peace Process Reaped Economic Dividends?," Israel at the Crossroads (1997): p. 23-64.

[6] Elie Podeh, "Israel and the Arab Peace initiative, 2002–2014: A plausible missed opportunity," The Middle East Journal 68, no. 4 (2014): p. 584-603.

[13] Benjamin Miller, "When and how regions become peaceful: potential theoretical pathways to peace," International Studies Review 7, no. 2 (2005): p. 229-267.

[14] Johan Galtung, "Theories of peace," A Synthetic Approach to Peace Thinking. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute (1967).

[15] Al-Monitor. “UAE-Israel trade.”

[16] Al-Monitor. “UAE-Israel trade.”

[17] Jaffe-Hoffman, “What is the future.”

[28] Harkov, “The UAE-Israel deal.”; Tovah Lazaroff, “Did UAE, Bahrain betray Palestinians by ignoring two-states in accords?”, The Jerusalem Post, 16 September 2020. https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/one-step-closer-to-palestinian-statehood-analysis-642409; Ariel Kahana, Reuters, AP, and ILH Staff, “'We brought hope to all the children of Abraham,'” Israel Hayom, 15 September 2020. https://www.israelhayom.com/2020/09/15/we-brought-hope-to-all-the-children-of-abraham/

[29] Eichner and Tzuri, “Israel makes history.”; Tovah Lazaroff, “Did UAE, Bahrain betray Palestinians by ignoring two-states in accords?,” The Jerusalem Post, 16 September 2020. https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/one-step-closer-to-palestinian-statehood-analysis-642409; Omri Nahmias, Lahav Harkov, Greer Fay Cashman, “Morocco, Israel normalize ties as US recognizes Western Sahara,” The Jerusalem Post, 11 December 2020. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/israel-morocco-agree-to-normalize-relations-in-latest-us-brokered-deal-651742; Hagay Hacohen, “Netanyahu: I will bring UAE investments to the Negev,” The Jerusalem Post, 19 August 2022. https://www.jpost.com/breaking-news/netanyahu-uae-deal-means-flow-of-investments-in-negev-639174

[32] Nahmias, “Morocco, Israel normalize.”

[35] Harkov, “The UAE-Israel deal.”

[36] Kahana and Daniel Siryoti, “Trump announces Israel,”; Eichner and Tzuri, “Israel makes history.”

[37] Kattan, “A fever dream.”