DOI: 10.58867/JPFX7559

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, energy dynamics have been reshaped within the context of an on-going global energy transition. Türkiye’s already built cross-border energy infrastructure has again underlined its geostrategic position. However, there are remaining challenges within the same context. This policy brief examines Türkiye’s energy relation with BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) through two dimensions: (i) Türkiye’s energy import dependency and its bilateral energy relations with Russia; and (ii) BRICS role in mediating power shifts in global energy politics.

Türkiye has taken advantage of its geostrategic location to promote energy diplomacy as part of its foreign policy efforts in adopting to changing security environment in its energy-rich neighborhood. Since the completion of the early cross-border pipelines, there have been changes and new developments in the energy market at the global level and energy geopolitics at the regional level. In the early 2000s, the East-West energy corridor, bypassing the Russian-controlled pipeline system, was a shared strategic priority between Türkiye and Western stakeholders to access crude oil/natural gas supplies in the Caspian region. Therefore, the inauguration ceremony for the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline in 2006 and the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum natural gas pipeline, which became operational in 2007, were major milestones in Türkiye’s efforts to diversify pipeline routes accessing the Caspian energy resources. Ankara’s policy goals were mainly to supply Türkiye’s growing energy demand and to foster regional interdependency.

Once these pipelines were in operation, the Turkish policy elite has increasingly promoted diversifying the European Union (EU) member states’ gas imports through Türkiye. Türkiye’s long-awaited aspiration to be an energy hub, thus, has evolved through different phases from a transit state or energy corridor to a regional energy trading center. There were limitations as a transit state. Although being a supplier country is not necessarily a condition to be an energy hub, there were difficulties in securing additional natural gas supplies from regional countries to deliver to the European energy market in the late 2000s (i.e., the Nabucco natural gas pipeline project).[1]

Within this context, energy dynamics in Türkiye’s relationship with BRICS countries present two major continuities. First, Türkiye has a growing energy market, given its relatively higher energy demand as a developing country. For example, Türkiye’s primary energy consumption between 2000 and 2020 increased on average annually by 3.1 percent, while the projected increase for the next period between 2020 and 2035 will be 2.2 percent.[2] Second, sunk-costs in existing pipelines (Blue Stream and Turk Stream) that deliver natural gas from Russia will continue to shape Türkiye’s domestic need for natural gas imports at least in the near term. More than 90 percent of Türkiye’s natural gas supplies are imported; and its total installed capacity and electricity production depend significantly on imported natural gas.

Continuities in Türkiye’s Asymmetric Interdependence with Russia in Energy Imports

Türkiye’s natural gas agreements with Russia in 1986 for the West Route and in 1997 for the Blue Stream pipelines aimed to meet Türkiye’s growing energy demand. The Blue Stream’s construction started in 2001, and gas flow began in 2003. Türkiye has gradually increased natural gas imports from Russia in parallel to its economic growth rate.

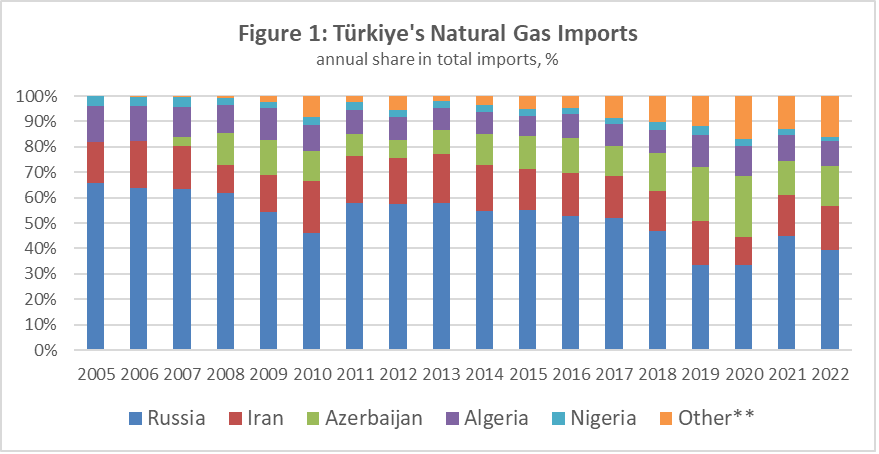

For example, Russian share in Türkiye’s total natural gas imports reached 54 percent in 2009, 58 percent in 2011, and 55 percent in 2015. These figures dropped to 34 percent in both 2019 and 2020. Two other sources replaced the decline in natural gas imports from Russia. First, Türkiye’s total natural gas imports from Azerbaijan increased to 21 percent and 24 percent in 2019 and 2020, respectively, from 14 percent in 2009 due to the completion of the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP). Second, the share of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Türkiye’s total natural gas imports increased to 28 percent and 31 percent in 2019 and 2020, respectively, from 15 percent in 2009 (See Figure 1).[3] Nevertheless, Türkiye’s continuing sensitivity to any natural gas disruption highlights asymmetric interdependence between Türkiye and Russia.

Natural gas has the second highest share after hydro in Türkiye’s total installed electricity capacity. Moreover, when there is a decline in Türkiye’s electricity production from hydropower (i.e., 30 percent, 26 percent, and 17 percent in 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively) due to drought, electricity production from imported natural gas increases (i.e., 19 percent, 23 percent, and 33 percent in 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively). [4] The start of domestic natural gas production from the offshore wells in the Sakarya field in the Black Sea since April 2023 is important to reduce risks in Türkiye’s pipeline-bound imports. However, it is insufficient for Türkiye’s current energy demand unless there are substitutes, especially in electricity production.[5]

Despite Türkiye’s asymmetric interdependence with Russia, Ankara and Moscow’s energy cooperation has continued during the changing geopolitics of the region, given Russia’s increasing use of force long before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 (i.e. the Russian-Georgian War in August 2008, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014, and Russia’s military intervention in Syria since September 2015). For example, Türkiye approved the Russian South Stream gas pipeline’s transit through the Turkish exclusive economic zone in the Black Sea shortly after signing the TANAP deal with Azerbaijan in 2011. Meanwhile, the EU Commission’s anti-trust investigation against Gazprom in 2012 induced Russia to abolish the South Stream project and redirect its proposed natural gas route to Türkiye, later known as the Turk Stream. Against this background, a memorandum of understanding was signed between Russia and Türkiye to build the Turk Stream natural gas pipeline in December 2014. The final agreement of the Turk Stream was signed in October 2016 after serious challenges for Turkish foreign policy and domestic politics.[6]

Türkiye’s energy cooperation with Russia expanded into the nuclear sector to build the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant since 2010. It continued despite some conflicting interests between Ankara and Moscow in regional disputes, such as Nagorno-Karabakh, Crimea/later Ukraine, Syria and Libya. In short, the complex relationship between Russia and Türkiye underlines continuities in Türkiye’s natural gas import dependency within the context of the changing regional security environment and President Erdoğan’s ever increasing power.

Türkiye’s Energy Dynamics and Shifting Paradigms in Energy Security

According to Türkiye’s National Energy Plan, the share of renewable energy sources in primary energy consumption, which was 16.7 percent in 2020, will increase to 23.7 percent by 2035. Nuclear energy, on the other hand, will reach a share of 5.9 percent by 2035. The share of fossil resources, which was 83.3 percent in 2020, will decline to 70.4 percent by 2035. The share of coal will decrease to 21.4 percent, and the shares of oil and natural gas will fall to 26.5 percent and 22.5 percent, respectively.[7] In fact, Türkiye has already made impressive progress in developing renewable energy sources led by hydro, solar, and wind.[8] In 2022 the share of renewables from wind, solar, and geothermal increased to 22 percent from 10 percent in 2018 in total electricity production capacity. The share of all renewable resources, including hydro and biomass, is 54 percent in total electricity production capacity in 2022.

In 2022, Türkiye revised its nationally determined commitment (NDC) by 21 percent to by 41 percent by 2030 and committed to net zero by 2053. Thus, Türkiye’s commitment to reducing emissions and its efforts to boost the share of renewables in electricity production underline both changes and challenges in Türkiye’s energy dynamics. Further, when we take into account the major trend in energy markets, namely electrification due to the growing share of the service sector in the world economy, the major challenge for Türkiye and BRICS is to be ready for new geographies of energy trade and to adopt to new energy security environment.

The on-going geopolitical crises in Ukraine and in the Middle East are merely an accelerator rather than driving forces shaping Türkiye and BRICS energy dynamics. For example, while the United States and the EU have sought to limit Russia’s energy exports following its invasion of Ukraine, Brazil, India and China largely abstained from changing their energy relationship with Russia. Hence, a major change in the energy security environment is shifting alliances built on fossil fuels. For example, since the Ukranian-Russian War, there has been an increasing share of American LNG in Europe’s energy security compared to Russia’s increasing natural gas exports to China by expanding the capacity of the Power of Siberia pipeline. The Power of Siberia was launched in 2019 and is projected to reach its maximum capacity by 2024. The pipeline transports natural gas supplies from newly developed gas fields in eastern Siberia. That means the pipeline does not divert the gas supplies that have been sent to Europe. Rather, the Power of Siberia-2 project aims to supply China from the gas fields in the Yamal peninsula. These gas fields used to serve the European market through several pipelines, including the Nord Stream-1 pipeline, before it was sabotaged in 2022. Similarly, the crude oil price wars between OPEC and Russia during the COVID-19 pandemic had forced many US shale oil producers on the brink of bankruptcy in 2020.

Lastly, recent attacks on shipping vessels by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in the Red Sea, a strategic choke point for crude oil, petroleum products, and LNG trade, have also disrupted tankers passing through the Suez Canal. The Bab-el Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are the fastest sea routes for both northbound and southbound destinations of energy trade. For example, rerouting of tankers from the Red Sea to around the coast of Africa adds about ten days longer to journey time. This is a severe concern for Europe and energy-important dependent India and China among BRICS. For example, India is a major importer of crude oil from Russia and a significant player in the export of petroleum products to Europe, both of which require transportation through the Suez Canal.

In short, Türkiye, China and India share common risks that can undermine the affordability and accessibility of fossil fuels in their energy-import-dependent economies. Türkiye should reconsider its energy diplomacy in the global energy transition context.

Conclusion: Türkiye and BRICS Role in Global Energy Politics

BRICS is an example of informal institutions or informal intergovernmental organizations that facilitate bargaining among states without freezing outcomes in permanent institutions while power transition in international politics evolves.[9] Thus, Türkiye and BRICS's commitment to net-zero targets is vital in fighting climate change and reconsidering energy diplomacy, given their mediating power in global energy politics.

In its 2021 report, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underlined that Türkiye will experience three accelerating trends: rising temperatures, dehydration, and rising sea levels. In fact, Türkiye has been experiencing more frequent and more severe weather conditions, such as heavy rain, wildfires, and drought throughout the year. Türkiye signed the Paris Agreement in April 2016. However, it was the last G20 country to ratify the Agreement in October 2022. Ankara’s argument for holding back from ratification of the Agreement for five years emphasized that it is historically responsible for a minimal share of carbon emissions. BRICS have also pledged their commitment to net-zero targets with submissions of their NDCs, albeit with some variation given differences in their energy market structure, size of their economy and demography.[10]

Accordingly, Turkish policymakers should consider the country’s role in global energy trade and its multilateral transportation policy, known as the Middle Corridor within the context of shifting paradigms in energy security and on-going energy transition.[11] Türkiye’s re-emphasis on its geostrategic position and its long-waiting aspiration to be a regional energy trade center should not be limited to re-balancing acts with non-western great powers, such as Russia and China in a U.S.-led liberal international order. Rather, understanding a multiplex international order, in which BRICS has proven its role in collaborating with like-minded partners in the critical cooperation areas (i.e. political economy, security and sustainable development) can help Türkiye’s energy diplomacy in changing the dynamics of energy trade. For example, the US and BRICS policy positions have converged in international renewable energy cooperation. However, the BRICS preferences regarding strengthening energy security cooperation internationally have been diverging from those of the US. [12]

Consequently, because of electrification, Türkiye’s energy dynamics and its energy diplomacy require an understanding ofregional energy infrastructure not only through pipelines but also through regional grids. There will be a gradual shift from global markets to regional grids because of electrification. Moreover, the projected share of renewables in electricity production, transportation, and hydrogen production is crucial for energy transition. This projection requires massive investment in domestic and cross-border grid infrastructure, given the intermittent availability of renewable energy sources and the need for non-renewable and/or non-fossil fuels, such as nuclear power in baseload plants or energy storage in grid systems. Therefore, through several mechanisms, Türkiye and BRICS can work together in international cooperation in renewable energy. For example, development banks and informal alliances among BRICS and Türkiye can facilitate bargaining among key regional partners for financing decentralized regional energy systems. However, a significant challenge for Türkiye and BRICS collaboration in boosting regional energy trade is fulfilling the high level of confidence required for sharing control on a regional grid system.

[1] For more information on how and under what conditions the Nabucco project was initiated by Türkiye and Austria; and despite an intergovernmental agreement in 2009 why the project was cancelled see Pınar İpek. (2017). “The Role of Energy Security in Turkish Foreign Policy (2004-2016)”in Turkish Foreign Policy: International Relations, Legality and Global Reach, Pinar Gozen (ed.) (Palgrave Macmillan US, 2017): p. 176-178.

[2] Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Türkiye National Energy Plan, 2022. https://enerji.gov.tr/Media/Dizin/EIGM/tr/Raporlar/TUEP/T%C3%BCrkiye_National_Energy_Plan.pdf, accessed 4 March 2024.

[3] Energy Market Regulatory Authority ‘s Natural Gas Sector Reports from 2005-2020.

[4] As of 2022 Türkiye’s total installed electricity capacity is distributed by 30.4 percent from hydro, 24.8 percent from natural gas, 10.9 percent from wind, 10.63 from lignite and coal, 9.9 percent from imported coal, 9 percent from solar, 1.6 percent from geothermal, 1.9 percent from biomass. Energy Market Regulatory Authority, Electricity Sector Report, 2022. https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/3-0-24/elektrikyillik-sektor-raporu, accessed 4 March 2024.

[5] The Project will be realized in two phases. In Phase 1, the daily production capacity will reach a maximum of 10 million cubic meter. That amounts to approximately 10 percent of summertime consumption and 4 to 5 percent of Türkiye’s wintertime consumption.

[6] Türkiye’s downing of a Russian fighter at the Turkish-Syrian border in November 2015 was a challenge for Turkish foreign policy and energy security. Though Russia introduced harsh sanctions against Türkiye, such as a set of restrictions on trade, there were no disruptions in the Russian gas exports to Türkiye. Nevertheless, negotiations between Türkiye and Russia on the Turk Stream were suspended in December 2015. Türkiye initiated investment in floating natural gas storage units to reduce risks for any disruption in natural gas imports from Russia. Russian-Turkish relations improved after the coup against President Erdoğan in July 2016.

[7] Türkiye National Energy Plan, 2022, p. 19.

[8] International Energy Agency, Turkey 2021 Energy Policy Review.

[9] Felicity Vabulas and Duncan Snidal. “Informal IGOs as Mediators of Power Shifts” Global Policy 11 Supplement 3, October 2020, p.40-50.

[10] Net zero targets of Brazil by 2060, Russia by 2060, India by 2070, China by 2060 and South Africa by 2050. Brazil and Russia submitted their NDCs in 2020, China and South Africa submitted their NDCs in 2021, while India submitted its NDC in 2016.

[11] Trans-Caspian East-West-Middle Corridor Initiative shortly named as “The Middle Corridor” begins in Türkiye and passes through the Caucasus region via Georgia, Azerbaijan, crosses the Caspian Sea, traverses Central Asia and reaches China.

[12] A recent study on “BRICS Convergence Index” measures policy convergence of the BRICS states using a novel data set of BRICS cooperation on 47 policy issues between 2009 and 2021. The findings of the study also demonstrate issue areas where BRICS and the U.S. converge or diverge. Mihaela Papa et al. “The dynamics of informal institutions and counter hegemony: introducing a BRICS Convergence Index,” European Journal of International Relations (2023) 29 (4): 960–989.