When international leaders meet in Paris in December this year, they will not only decide on international climate policy. They will also negotiate the world’s energy future. Fossil fuel combustion is responsible for roughly two-thirds of past and future global carbon dioxide emissions.[1] Current ways of producing and consuming energy would result in a warming of at least 3.6°C.[2] If the international community wants to limit global warming to 2°C, emissions from the energy sector need to be reduced radically. The 2°C objective, in short, translates into the de-carbonization of the world’s energy use. The EU, for example, assumes in its roadmap for moving to a low-carbon economy that developed countries need to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95 percent by 2050. Even such radical measures, however, will not be enough to fight climate change effectively.

Other states need to contribute to a global solution, too. This is particularly true for emerging economies such as China, India, and Brazil. They are key to global energy transition, because the profound economic transformation they are experiencing calls for substantial investments in energy infrastructure. Investment decisions that are made today will lock in the structure of their growing energy systems for the coming decades. Turkey shares important characteristics with these countries regarding both its dynamically growing economy as well as the challenge of providing secure and affordable energy. Turkey, too, is in the process of building up energy systems and infrastructures that will determine the country’s energy future.

To move to a low-carbon economy, developed countries need to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95 percent by 2050 [according to the EU roadmap].

Turkey’s leaders aspire to make the country an increasingly important player in international relations. One important element of this aspiration is to make Turkey one of the world’s 10 largest economies by 2023. A secure and affordable supply of energy is essential to realize this aim. Turkey’s ambitions to become a more important player on the international stage are therefore intrinsically linked to its domestic energy policies.

In a context of growing demands for serious climate action, however, secure and affordable energy is not enough anymore. Sustainability is becoming increasingly important for international reputation.

This could become a significant impediment to Turkey’s international standing in the future – within but also beyond the policy fields of energy and climate. A country that is primarily focused on coal and other fossil energy resources risks a severe loss in international standing. As long as a larger Turkish economy is a dirty one, it might not result in growing international importance. For long-term international leadership, therefore, Turkey should develop a genuinely sustainable energy strategy.

How Will Energy and Climate Governance Look in the Future?

Turkey is changing rapidly, and is right to aspire a leading position in the international system. However, not only Turkey is changing, so is its international environment. If Turkey’s ambitious foreign policy agenda is to be successful, it needs to take into account these external changes. Otherwise, Turkey risks preparing for a world that has moved ahead when the benefits of its strategy are supposed to kick in. If Turkey wants to become a leading actor in international politics, it needs to ask itself: what will the future of international politics look like?

Answering this question is tricky business since, quite obviously, the future has not yet happened. Dealing with the future always means grappling with uncertainty. Often times, moreover, the politics of the day seem to obscure the long view. There is a chance, for example, that nothing significant will come out of Paris. This, some commentators might argue, could signal the end of international climate policy. Such an evaluation, however, would underestimate trends in the energy and climate fields that make some futures more and others less likely.

Perhaps the most certain and important trend is that of ongoing climate change. There is no way to actually reverse climate change. Climate policy instead merely aims to limit the degree of global warming, and the physical facts seem to tell us that actual global warming might end up well above 2°C.[3] The socioeconomic impacts of climate change are expected to become an increasing burden for the world economy, global development, and security.

Turkey’s ambitions to become a more important player on the international stage are intrinsically linked to its domestic energy policies.

Regardless of what happens in Paris, climate impacts are very likely to increase the societal and political pressure to agree on significant adaptation and mitigation measures in the medium and long run – on the international and national societal levels. Carbon pricing and emission trading systems, for example, are likely to become more important. Despite some practical problems and setbacks (such as in Australia), such systems are already being developed and operated in places such as the EU, the US, and China.[4] In the future, pressure might increase to install similar systems in other regions too. Not meeting such demands would likely result in a loss of international reputation since it would render the refusing actor unsustainable and potentially reckless. In the future, ambitious promoters of sustainability might even push for greenhouse gas-specific trade measures to compensate for the extra costs of carbon pricing and keep dirty products off their markets.

Hard coal and low-energy content lignite – the dirtiest of conventional fossil fuels – will be hit particularly hard by these trends. Already today, coal is losing its appeal. Policymakers have become wary of societal protests against coal-fired power plants, and investors see risks deriving from coal’s negative environmental and climate impact as well as its vulnerability to future climate policy. The latter has spurred a growing divestment movement. In particular, investors with a long-term view are moving out of coal; prominent names include the universities of Stanford and Oxford, the French insurance company AXA, and the sovereign wealth fund of Norway.

A parallel trend is that renewable energies such as wind and solar energy become increasingly attractive to governments and investors alike. On a global scale, renewable energy investment has become a market almost as big as and more dynamic than that for fossil fuels.[5] While climate policy can be expected to add to the cost of fossil energy, dynamic market developments will likely make renewables increasingly cheaper in the future. As climate action becomes more eminent and sustainable energy solutions become cheaper, sustainability is bound to become increasingly important in international politics.

Is Turkey Fit for a More Sustainable Energy Future?

Turkey’s economy has been growing almost twice as fast as OECD countries on average over the last 10 years.[6] Besides bringing benefits to its citizens, economic strength has long been understood as a major power asset in international politics.[7] Turkey’s leadership thus likes to highlight its country’s economic performance. It is also well aware of the role that energy plays in this context. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, for example, has recently stated: “We need to increase our energy consumption rapidly.”[8] Already today, as Turkey’s officials like to emphasize, the Turkish growth in energy demand is second only to China.

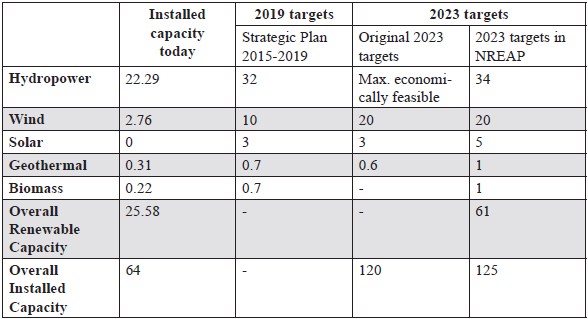

To meet future energy needs, Turkey has formulated an ambitious energy plan, envisaged to be realized by 2023.[9] The original plan aimed to increase installed power capacity to 120 GW and to add 18.5 GW of coal-fired capacity as well as nuclear power facilities to the energy system. Renewable energy sources were envisaged to contribute 30 percent to electricity generation. The use of hydropower was envisaged to be expanded to its maximum economically feasible potential; wind energy capacity was planned to be raised to 20 GW, solar capacity to 3 GW, and geothermal capacity to 600 MW. The more recent Energy Ministry’s Strategic Plan for 2015-2019 and the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP) have specified and updated some of these numbers (see: Figure 1).

Figure 1: Renewable Energy Policy Targets of Turkey in GW

Source: Installed capacity and NREAP 2023 taken from the NREAP, 2019 targets taken from the Strategic Plan 2015–2019, original 2023 targets taken from Invest in Turkey, Energy and Renewables.

The NREAP deals primarily with the role of renewable energy in Turkey. The plan holds that Turkey aims to expand its renewable energy production capacity from 25.58 GW in 2013 to 61 GW in 2023. And indeed, it raises the targets for some renewable energy sources such as solar, geothermal, and biomass (see: Figure 1).

These numbers suggest that Turkey is well prepared for a future international environment in which sustainability is likely to become a constant and major theme, and not just in climate and energy policy. However, as discussed in the next section, problems arise both in terms of implementation as well as regarding the overall energy mix that is envisaged by Turkey.

Spoilers: Low Non-Hydro Share, Implementation Deficit, and Coal

The NREAP numbers appear to signal an increasing focus on renewable energy and might thus raise hopes of a sustainable Turkish energy future. Nevertheless, the practice of Turkish energy development shows a somewhat different picture.

First, non-hydro renewable energy capacity is less impressive that it might appear at first sight. It totaled 3.29 GW in 2013 and is expected to rise to 27 GW in 2023. The great reliance on hydropower has been criticized repeatedly. Hydro projects can change river flows and negatively affect ecosystems. The flooding of land can lead to relocations of local populations as well as to the loss of agricultural land and cultural sites. Such problems have become apparent, for example, in the context of the construction of the Ilısu Dam in Southeast Turkey. Furthermore, hydropower has been argued to be vulnerable to changing patterns of precipitation and water runoff, as they are provoked by climate change.

Turkey aims to expand its renewable energy production capacity from 25.58 GW in 2013 to 61 GW in 2023.

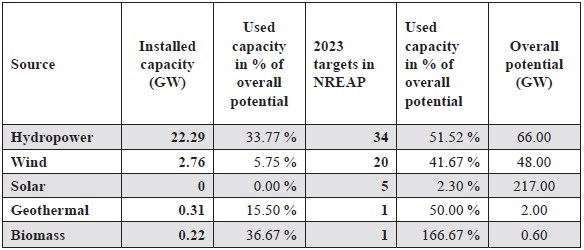

Non-hydro renewables targets are furthermore comparatively unambitious given Turkey’s great renewable energy potential.[10] Turkey ranks first amongst European countries with regard to hydropower, wind, and geothermal potential and second with regard to solar power potential.[11] While hydropower capacity is used most extensively, there is ample room for improvement regarding all other forms of renewable energy. Taken together, more than 90 percent of Turkey’s renewable energy potential remains untapped. Even if the NREAP goals should be reached, Turkey would still use less than 20 percent of its available renewable energy potential (also see: Figure 2).

Figure 2: Policy Targets and Installed Capacity Compared to Turkey’s Overall Renewable Potential

Source: For installed capacity and goals, see: Figure 1. Overall potential taken from Energy Charter Secretariat, In-Depth Energy Efficiency Policy Review of The Republic of Turkey

Despite this great potential, a recent study of Bloomberg New Energy Finance contends that Turkey risks missing its own renewable energy targets.[12] This points towards a second spoiler for a sustainable energy future in Turkey: the implementation of renewable energy targets has proven to be challenging in practice. Support through feed-in tariffs is considered to be too low, too short (10 years), or not flexible enough by voices from environmental organizations and industry, as well as by some individuals from the administration.[13]

Commentators have furthermore identified substantial bureaucratic hurdles to renewable energy investment. Particularly the licensing of new projects has been argued to be too complex and time consuming, which has frustrated both small local and larger international investors.[14] As some international investors have put it, licensing has been conducted in ways that have “put off” investors “prepared to commit to ‘gigawatts of generation’ over a long-term horizon.”[15] Despite the phenomenal growth of its overall energy market, the attractiveness of Turkey for renewable energy investment is average at best. In Ernst & Young’s Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index, Turkey ranks 19th out of 40 states.[16]

While sustainable energy development in Turkey is thus not being pursued to its full potential, the third and greatest spoiler regarding a sustainable Turkish energy future is the country’s treatment of other, non-renewable energy sources. These are specified in the Energy Ministry’s new Strategic Plan for 2015-2019. The share of natural gas in electricity generation should decrease from 43.8 percent in 2013 to 38 percent in 2019. Additional capacity is going to come from nuclear power. Following the Plan, a test phase of generation shall be started for the Akkuyu nuclear power plant by late 2019.

The major portion of new electricity, however, is predicted to come from domestic coal. It is planned to be increased from 32.9 bn kWh in 2013 to 60 bn kWh in 2019. Hard coal and particularly low-energy content lignite thus play an important role in the Turkey’s energy strategy. Recent research suggests that, in contrast to renewable energy targets, the coal target of an additional 18.5 GW will be more than fulfilled with almost 37 GW of new coal-fired generation capacity being planned in Turkey.[17] The financing of coal projects is said to have become one of the Turkish banking sector’s priorities, and governmental financial support for coal substantially exceeds financial help for renewable technologies.[18]

Despite all progress with regard to renewable energy sources, this focus on coal is a huge burden for the sustainability of Turkey’s energy systems. If the Turkish government should follow through on its coal policies, this might increase energy sector carbon emissions by almost 150 percent by 2023.[19] A “dash for coal,” to put it more bluntly, would be a certain death knell for any attempt to become a truly sustainable energy economy.

Implications for Turkey’s Long-Term Standing in International Relations and Ways Ahead

In the face of the upcoming Paris climate summit, important actors have moved forward with ambitious climate and energy plans – the EU has decided on new climate and energy targets for 2030, and US President Obama has recently announced a Clean Power Plan to substantially reduce carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. These measures will not be a nine day wonder, thougher action on climate change is here to stay. Intensifying climate change and its socioeconomic impact will put increasing pressure not only on industrialized states, but also on other members of the international community to commit to engage in meaningful climate policies and sustainable energy transition.

International climate policy can be expected to make fossil resources more expensive, while dynamic market developments suggest further cost cuts for renewable energy sources. Investors are likely to adapt to these trends. Important players in this sector are already divesting from coal. All these trends point towards an international system in which sustainability will become increasingly important.

In the future, therefore, important players will need to be sustainable players. States that defy the increasing pressure for serious climate action and energy transition, in contrast, will be increasingly perceived not only as anachronistic, but also as harming the rest of the world. Resistance to adopting sustainable energy policies could thus signicantly reduce these states’ international reputation.

Turkey ranks first amongst European countries with regard to hydropower, wind, and geothermal potential and second with regard to solar power potential.

In this situation, Turkey’s aspiration to become an important player on the international stage would be compromised by its strategy to secure affordable energy for its economy at home. Should the latter be provided by a significant extension of coal power plant capacity, this would significantly reduce the country’s credibility as a sustainable economy and a forward-looking political actor in the future.

To preserve and actually strengthen its prospect of becoming an important international actor in the future, therefore, Turkey should develop a genuinely sustainable energy strategy. It should seriously re-consider its position on coal and make greater efforts to realize its tremendous renewable energy potential.

The bad news is that, if appropriate choices are not made today, Turkey will be trapped in its fossil energy systems for decades. Reversing this course in the future will be possible only at a great cost. The good news is that a variety of helpful strategies are already listed in the NREAP and the Action Plan 2015-2019. The implementation of strategies for renewable energy promotion, energy efficiency, and enhancing the Turkish investment environment that are listed in these documents should be made a priority of Turkey’s energy policy. Ultimate efforts, however, must go beyond these measures and tackle country’s flawed approach to coal.

[1] “Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policymakers,” IPCC, p. 12, http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_SPM_FINAL.pdf

[2] “Re-Drawing the Energy-Climate Map. World Energy Outlook Special Report,” IEA (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2013), p. 26, http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/weo_special_report_2013_redrawing_the_energy_climate_map.pdf

[3] “Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Summary for Policymakers” (2013), p. 12.

[4] In Australia, the conservative government of Prime Minister Tony Abbott managed to slash the country’s carbon tax and plans for emissions trading in 2014. The move provoked harsh domestic criticism as well as criticism by international partners.

[5] “Renewables 2014. Global Status Report,” Renewable Energy Policy Network, 2014, pp. 72-101.

[6] Following OECD data, the average growth of the OECD as a whole was 1.41 percent per year between 2006 and 2015. Turkey’s average annual growth was 3.76 percent during the same period. OECD.Stat, http://stats.oecd.org/

[7] Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

[8] “Turkey Needs to Invest $120 Billion in Energy until 2023, Says Erdoğan,” Hurriyet Daily News, 20 January 2015, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-needs-to-invest-120-billion-in-energy-until-2023-says-erdogan.aspx?pageID=238&nID=77197&NewsCatID=348

[9] “Energy and Renewables,” Invest in Turkey, http://www.invest.gov.tr/en-US/sectors/Pages/Energy.aspx

[10] “Turkey’s Changing Power Markets. White Paper,” Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 18 November 2014.

[11] Kemal Barış and Serhat Küçükali, “Availability of Renewable Energy Sources in Turkey: Current Situation, Potential, Government Policies and the EU Perspective,” Energy Policy, Vol. 42 (March 2012), p. 376.

[12] “Turkey’s Changing Power Markets” (2014), p. 4.

[13] Barış and Küçükali (2012); Paul Gipe, “Turkey Adopts Limited Feed Law Turkey’s Parliament Has Revised Its Limited Feed Law with Adoption of a Similarly Limited Policy,” Renewable Energy World, 17 January 2011, http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2011/01/turkey-adopts-limited-feed-law ; Mustafa Gözen, “Renewable Energy Support Mechanism in Turkey: Financial Analysis and Recommendations to Policymakers,” International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, Vol. 4 (2014); Jennifer Hattam, “Renewables Law Unlikely to Tap Turkey’s Potential,” Treehugger, 8 January 2011, http://www.treehugger.com/renewable-energy/renewables-law-unlikely-to-tap-turkeys-potential.html

[14] Selahattin M. Şirin and Aylin Ege, “Overcoming Problems in Turkey’s Renewable Energy Policy: How Can EU Contribute?,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 16, No. 7 (September 2012), pp. 4923-4924, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.03.067

[15] Kristy Hamilton, “Investing in Renewable Energy in the MENA Region: Financier Perspectives,” Chatham House EEDP Working Paper, 1 June 2011; also see: “Turkey’s Renewable Energy Sector from a Global Perspective," Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2012, https://www.pwc.com.tr/tr_TR/tr/publications/industrial/energy/assets/Renewable-report-11-April-2012.pdf

[16] “RECAI Scores and Rankings at September 2014,” Ernst&Young, 2014, http://www.ey.com/UK/en/Industries/Cleantech/Renewable-Energy-Country-Attractiveness-Index---Index-highlights

[17] Ailun Yang and Yiyun Cui, “Global Coal Risk Assessment: Data Analysis and Market Research,” World Resource Institute, November 2012, p. 5, http://www.wri.org/ publication/global-coal-risk-assessment

[18] Anelia Stefanova and Daniel Popov, “Black Clouds Looming. How Turkey’s Coal Spree Is Threatening Local Economies in the Black Sea,” CEE Bankwatch Network, October 2013, pp. 5, 16.

[19] Stefanova and Papov (2013), p. 4.