With the Syria crisis in its sixth year, humanitarian aid and the absorption capacity of Jordanian communities have become stretched. Due to the difference between their income and expenditures and with limited access to sustainable livelihood options, many refugees have now entered a cycle of asset depletion, with savings gradually exhausted and levels of debt rising.[1] The most vulnerable refugees are particularly affected, with many increasingly adopting negative coping strategies, including a reduction in food consumption, withdrawing children from school, and taking on informal, exploitative, or dangerous employment. A number of reports highlight the significant impact of the Syrian refugee influx on the Jordanian labor market, and there are strong concerns about its effect on job opportunities, wage levels, working conditions, and access to work, for Jordanians, refugees, and immigrant workers alike.[2] This is of particular concern in the northern governorates, where the concentration of Syrian refugees and pressure on the labor market is most severe.

Only about 10 percent of employed Syrians have actually obtained formal work permits.

Jordan is not a signatory of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, and in the first three years of the crisis, it has largely maintained an open door policy whereby Syrian refugees can freely enter the country. As a result, Jordan has been significantly affected by this population influx as it is currently hosting unprecedented numbers of Syrian refugees. While these refugees are not automatically granted the legal right to work, they have been putting additional strain on the already fragile labor market, which has further exacerbated existing tensions with local communities.[3] This paper aims to first, highlight the legal contexts of Syrian refugees, and secondly, provide an overview of the provision of social protection to Syrians in Jordan, including the challenges they are facing in gaining access to the formal labor market and social protection mechanisms. It will conclude by providing policy recommendations that outline the role of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in supporting Syrian refugees in Jordan.

Employment Policy for Syrian Refugees

In light of the large influx of Syrian refugees into the country, a 2015 study revealed staggering employment statistics. About 51 percent of Syrian men residing outside the refugee camps participate in the Jordanian labor force, and the unemployment rate is as high as 57 percent.[4] For women’s unemployment, this figure lies at 88 percent. However, only seven percent of Syrian women participate in the Jordanian labor market, a statistic similar to Syria’s pre-conflict female unemployment rate of 28 percent. At present, more than 40 percent of Syrian refugees employed in urban areas (such as Amman, Irbid, and Mafraq) work in the construction industry, with 23 percent working in the wholesale and trade 12 percent in manufacturing, and eight percent in the accommodation and food service industry. Another key finding is related to the issue of the right to work in Jordan. Despite these figures, only about 10 percent of employed Syrians have actually obtained formal work permits. This means that 99 percent are working in the informal economy and thus outside the bounds of Jordanian labor law. The implications of this should be viewed from the perspective of the expanding informal employment sector, which is characterized by low and declining wages, longer working hours, and poor working conditions and regulations – including a lack of proper work contracts.[5] 96 percent of refugees outside of the camps and 88 percent of refugees in Zaatari camp have no social insurance specified in their employment contract. As Syrian employees are not given a formal work contract, there is a great difference between refugee and host communities when it comes to the provision of social insurance.

Child labor is substantially more prevalent among Syrian children than among Jordanian children. Only 1.6 percent of Jordanian boys aged 9-15 are economically active, while more than eight percent of Syrian boys in the same age group are. Among those between the ages of 15-18, about 37 percent of Syrian boys are (informally) employed, compared to about 17 percent of Jordanian boys. Almost 14 percent of Syrian boys ages 15-18 are employed, compared to eight percent of Jordanian boys in the same age.

According to UNHCR estimates, it is expected that approximately 15 percent of these refugees will remain concentrated in refugee camps. Over 80,000 Syrian refugees currently reside in Zaatari Refugee Camp, located in Jordan’s Mafraq Governorate.

The labor market within Zaatari camp is restricted to a limited number of opportunities, and as a result the unemployment rate is at approximately 80 percent.

According to a 2015 ILO survey titled, “The impact of Syrian refugees on the labor market in Jordan,” more than eight in 10 workers living in the camp work inside the camp, and while interviews confirm that employers have indeed recruited refugees from the camp in the past, survey results suggest this practice is declining. Currently, the labor market within Zaatari camp is restricted to a limited number of opportunities, and as a result the unemployment rate is at approximately 80 percent. Survey results indicate that those who do find a job, work with market stall enterprises, which are the primary employment options in camp. In terms of employment trends in and outside of Zaatari camp, a larger share of refugees in Zaatari camp work in the transportation and food service industry, with an equally high share working in the retail sector. 99 percent of refugees are employed informally in Zaatari. There are also volunteer positions under cash-for-work schemes that are being organized by UN agencies and NGOs and constitute a source of income for 19 percent of the refugees. However, these positions are set at a standardized rate of one Jordanian dinar per hour for unskilled labor and 1.5 Jordanian dinars for skilled labor.

Jordan Compact

The Jordan Compact plan proposes improving access to formal employment opportunities for Syrian refugees within the context of economic growth, which in turn creates more jobs that can benefit both Jordanians and Syrians. The aim of the compact, presented by the Jordanian government at a conference titled “Supporting Syria and the Region” in London on 4 February 2016, was to change the macro-level conditions for job availability in the country through radical improvements in trade and investment, in order to boost employment and accommodate the participation of Syrians in the labor market. These macro-level changes will impact various sectors differently, depending on the skill levels, type of job, and in cases where quotas regulate the number of employed Jordanians.

The Jordan Compact rests upon three interlinked pillars aimed at supporting Jordan’s growth agenda, while maintaining its resilience and economic stability:

- Turning the Syrian refugee crisis into a development opportunity that attracts new investments and opens up the EU market with simplified rules of origin, and creating jobs for Jordanians and Syrian refugees while supporting the post-conflict Syrian economy;

- Rebuilding Jordanian host communities by adequately financing the Jordan Response Plan 2016-2018 with grants, particularly the resilience of host communities;

- Mobilizing sufficient grants and concessionary financing to support the macroeconomic framework and address Jordan’s financing needs over the next three years, in connection with Jordan entering into a new Extended Fund Facility program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Jordanian government is committed to improving its business and investment environment, and is moving forward with a detailed plan on what measures, changes to regulation, structural reforms, and incentives can be offered to domestic and international businesses. An integral part of incentivizing businesses is through access to European markets under easier terms than those currently available. The government has developed a pilot project to designate 18 development zones and provide these with maximum incentives under the new investment law. These have the potential to create additional jobs for both Jordanians and Syrian refugees. In addition to the existing preferential access for Jordanian products in the EU market, such as zero tariffs and no quotas for most traded goods, the new agreement signed between Jordan and the EU relaxed the rules of origin, which means a greater number of jobs are likely to be created.

Jordan is committed to undertake the necessary administrative changes to allow Syrian refugees to apply for work permits both inside and outside of the above-mentioned 18 development zones. These will be renewed annually in accordance with prevailing laws and regulations. In addition, Syrian refugees will be allowed to formalize their existing businesses and to set up new ones, including access to investor residencies, in accordance with the existing laws and regulations.

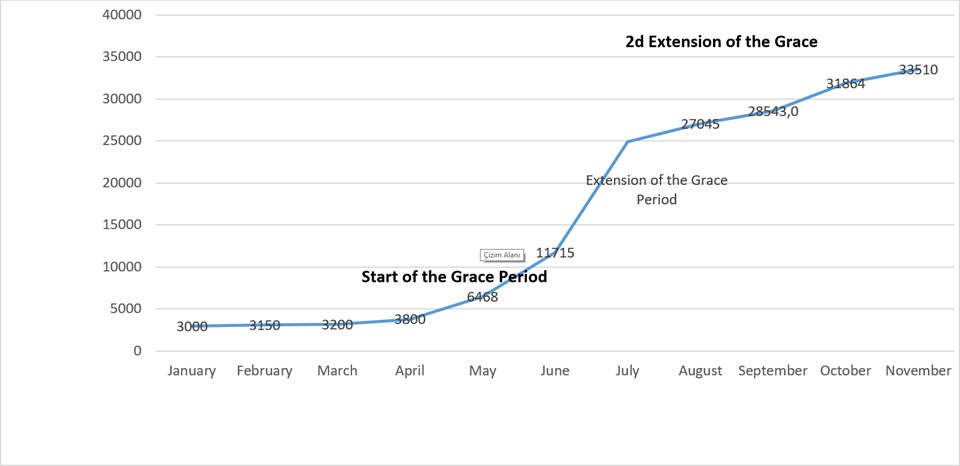

Several policy decisions have been implemented to stimulate labor market opportunities for Syrian refugees and Jordanians, including a moratorium in June 2016 on new migrant workers entering Jordan. In addition, as of April 2016, the Ministry of Labor (MOL) allowed a grace period of three months for Syrian refugees working without a work permit to regulate their employment status, which has been extended to the end of 2016. This included waiving fees related to obtaining a permit to mobilize refugees and employers alike and accepting the Ministry of Interior (MOI) identity card instead of a passport.[6]

The ILO’s Response to the Jordan Compact

The ILO has been working with agricultural cooperatives in Jordan since May 2016 – with the goal of formalizing the sector – in which a large number of Syrian refugees are currently employed. When the government of Jordan made the decision earlier this year to give Syrian refugees a three-month grace period to apply for work permits, the number of applicants was small. In response, the ILO held discussions with Syrian refugee farmers and found that, despite the latest measures, a dearth of employers willing and able to process the paperwork was the main reason for the slow hiring.

The Jordan Compact plan proposes improving access to formal employment opportunities for Syrian refugees.

Through these efforts, trust has been built between members of the refugee community and individuals within the cooperatives, allowing them to work closely together. Through work permits, cooperatives have now generated a database of Syrian workers eligible for work within specific sectors, and are thus taking on the role of employment offices and helping facilitate the process of recruitment services and job matching. In return, this has allowed cooperatives to gain recognition from the government, particularly the MOL and from NGOs working to help improve refugee access to the labor market.

With support from the ILO and others through advocacy and rising awareness, as well as partnerships with sector organizations, the number of work permits being issued for Syrian refugees sharply increased to almost 33,500 by early December 2016.

Source: MOL

As a result, the MOL, in consultation with the ILO, introduced a new model that includes unlinking the work permit application process from specific employers in the agricultural sector, and allowing cooperatives themselves to apply for Syrian refugee work permits. This enables these cooperatives to act as the “employers” or “mediators” in the work permit process.

Cooperatives are now performing the paperwork themselves at the local MOL authorities so that the workers do not have to do it, which has been a great incentive for them. At the same time, the cooperatives have also been helping the labor directorates by holding informal campaigns instructing workers on how to apply for work permits, as well as on their rights and entitlement under labor laws.

Many infrastructure projects started contacting cooperative offices to match them with Syrian refugee job-seekers. This approach can significantly mitigate the adverse impact of the Syrian refugee crisis on the livelihoods of vulnerable people in the most affected governorates in northern Jordan, namely Mafraq and Irbid. It will support the creation of immediate job opportunities for vulnerable groups, as well as medium-term economic and employment opportunities through employment-intensive and local resource-based infrastructure development.

Boosting Skills and Work Permit Applications in the Construction Sector

In the construction sector, the ILO is also helping workers obtain occupational certificates and social security enrollment. Syrian workers in the construction sector are self-employed and are working without work permits due to the absence of employers willing to go through the effort and expense of applying for these permits. Therefore, in order to help these workers become formally employed, they need an entity rather than an employer, such as an official employers organization to facilitate their access to work permits.

The ILO has been working with agricultural cooperatives in Jordan since May 2016 – with the goal of formalizing the sector – in which a large number of Syrian refugees are currently employed.

Therefore, the ILO has partnered with the National Employment and Training (NET) Company to provide short courses for Syrians and Jordanians in floor laying, painting, plastering, plumbing, and interior decoration. The courses help the refugees upgrade their professional expertise and obtain accredited skills certificates, which in turn enables them to enroll in Jordan’s social security scheme for the self-employed. This combination of upgraded skills and social security protection increases their employability, and helps them to attract official organizations that can apply for work permits on their behalf and legalize their employment status.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Today, Syrian refugees in Jordan have better chances in accessing formal employment, especially after the Jordan Compact was drafted. However, greater effort is required to ensure that the push for decent jobs in the formal economy related to the EU trade deal is matched by a comparable effort for the informal economy, especially the construction and agriculture sectors. This can be achieved by:

- Facilitating the creation of a more conducive regulatory framework that would increase wage and self-employment opportunities for both Syrian refugees and host communities. The improvements to the regulatory framework in order to improve both job matching and compliance to the labor code will rely on clear evidence that can be created by an observatory for the labor market. This observatory will implement a continuous stream of qualitative and quantitative research related to (a) labor market demand, and (b) the impact of the changes in regulatory framework on the employment of Syrians.

- More evidence generated on the attitudes of Syrians to the labor market and the driving factors in order to design incentives that can help to provide proper career guidance for them. An evidence-based approach to revising labor quotas and the list of closed occupations enables educated Syrians to work in strategically selected sectors, thereby lowering the investment cost for job creation.

- Strategic channeling of London pledges to investment in sectors and projects where Syrian workers have the best potential to contribute to a more robust and competitive economic architecture, such as labor-intensive infrastructure projects, support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and innovation projects, and training programs.

[1] “Baseline study on Vulnerabilities Assessment Framework VAF,” UNHCR, 2015,

[2] Maha Kattaa, “Social protection and employment for Syrian refugees in Jordan,” Conference of Regulating Decent Work Networks, 2015, http://www.rdw2015.org/uploads/submission/full_paper/20/Social_protection_and_employment__the_case_of_Syrian_refugees_in_Jordan.pdf

[3] “Access to work for Syrian refugees in Jordan: A discussion paper on labour and refugee laws and polices,” ILO Regional Office for Arab States, 2015, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---arabstates/---ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_357950.pdf

[4] Svein Erik Stave and Solveig Hillesund, “Impact of the influx of Syrian refugees on the Jordanian labor market: Findings from the governorates of Amman, Irbid and Magraq,” ILO and FAFO, 2015.

[5] Svein Erik Stave and Maha Kattaa, “Labour force and unemployment trends among Jordanians, Syrians and Egyptians in Jordan 2010-2014,” International Labour Organization (ILO), http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---arabstates/---ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_422561.pdf

[6] “Results of Focus Group Discussions on Work Permits with Syrian Refugees and Employers in the Agriculture, Construction & Retail Sectors in Jordan,” International Labour Organization (ILO), 2016, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---arabstates/---ro-beirut/documents/briefingnote/wcms_481312.pdf