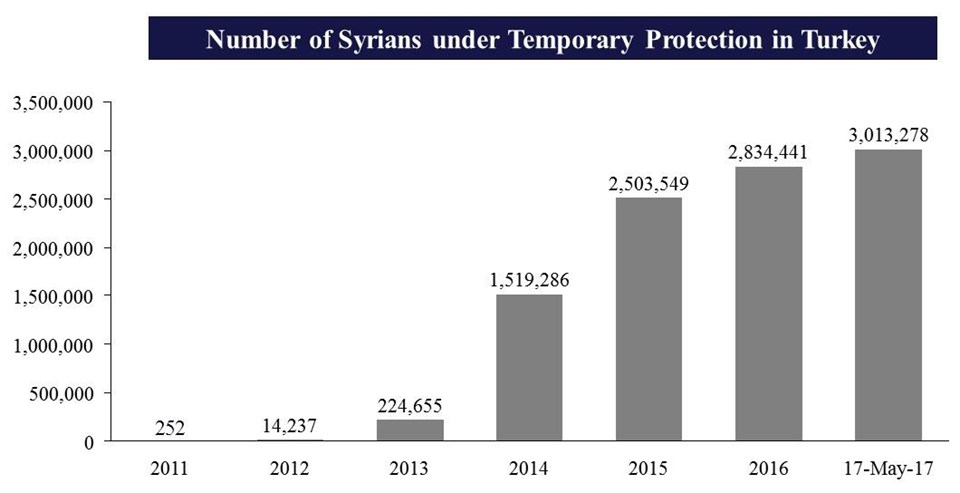

It was April 2011 when the first group of Syrians crossed the border into Turkey. The 252 Syrians who moved to the town of Yayladağı, Hatay came from villages adjacent to the Turkish border.[1] They were fleeing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad regime’s brutal suppression of protests that were erupting across the country. In the months and years that followed, hundreds of thousands of Syrians approached the Turkish border, with a majority coming from Northern Syria, and a smaller group from the southern provinces, including big cities like Damascus.[2] Seven years into the war, Turkey is hosting over three million Syrians (see figure one).[3]

In January 2016, Syrians under Temporary Protection were given the right to work, albeit under stringent conditions.

It took a few years for the Turkish state to make the necessary legal adjustments. Turkey maintains a geographical limitation to Geneva’s 1951 Refugees Convention, which means it can grant refugee status only to those seeking asylum “due to events unfolding in Europe,” referring to World War II. This is why Syrians were officially called “guests” at the onset. They did not have any legal status, and though they were welcomed by the government, there was no policy framework to oversee them. In April 2013, the Turkish Parliament ratified the Law of Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP), and the Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) was established. Syrians could now be granted Temporary Protection (TP) status, which provided them with access to basic public services such as health and education, and, to a lesser extent, access to the labor market.[4]

In January 2016, Syrians under TP were given the right to work, albeit under stringent conditions. In order to be legally employed, a Syrian needs to have been under TP for six months, work only in the province he or she is registered under, and be doing work that no eligible Turkish citizen is interested in. Employers are also not allowed to have more than 10 percent of their labor force be Syrian.[5] Over the course of 2016, only 13,300 Syrians were granted work permits, with the vast majority working in the informal sector, earning well below the minimum wage.[6] These developments mean that there is now a legal framework, however it is only gradually being implemented.

Figure 1: Number of Syrians under Temporary Protection in Turkey

Source: Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) and T24

Today, nine out of 10 Syrians live outside of the camps that have been set up by the government, with many having migrated to large cities in inner Anatolia or Western Turkey – and also Istanbul. Istanbul’s Fatih district, for example, has long been known for being conservative, but today it also has a pocket called “Küçük Suriye” meaning, “Little Syria.” Walking through Little Syria, the first thing one will notice is that the restaurant signs and street chatter is in Arabic. Just as a Turk arriving in Berlin in the 1980s first made his way to Kreuzberg, (dubbed “Little Istanbul”) so too will a Syrian arriving in Istanbul first go to Little Syria, most likely to reunite with his or her relatives. And just as migrants going to Europe, some Syrian communities move to different parts of Turkey. Many Syrians from Latakia have settled in “Küçük Lazkiye” in the city of Mersin, while people from Aleppo are likely to be found in “Küçük Halep” in Ankara.[7]

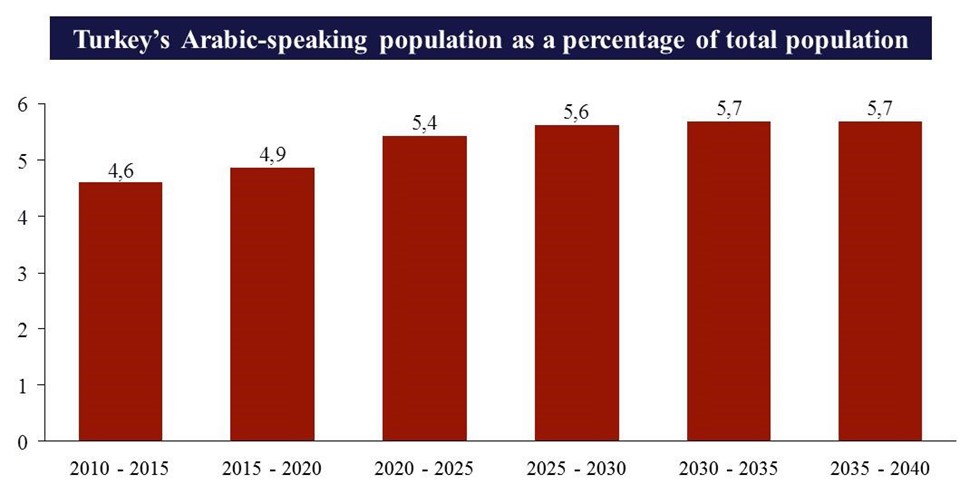

Currently, Syrians already make up about 3.6 percent of Turkey’s population. Taking into account Syrian demographic trends, by 2040, almost five percent of Turkey’s population will be made up of people of Syrian origin. If one adds Arabic speaking Turkish citizens in Hatay to this number, almost six percent of Turkey’s population will be native Arabic speakers (see figure two). This would make Arabic speakers the third largest linguistic group after Kurdish (Kurmanci) speakers. Since Syrians do not have a tradition of agriculture in Turkey, much of this population will likely live in cities, and therefore have an outsized influence on the country’s day-to-day life.

Figure 2: Turkey’s Arabic-Speaking Population as a Percentage of the Total Population

Source: UNDP, TEPAV calculations

The last time Turkish cities absorbed refugees on this scale was during the early years of the Republic, when Muslim populations from the Balkans made their way into the country. This is the first time since World War II that Turkey is host to such large numbers of refugees. We can reflect upon this in two ways.

The first is that given the fact that Syrians and Turks come from the same “civilization,” Syrians are able find their place in Turkey without much social conflict. People of this mindset point towards the great generosity and patience of the Turkish population in receiving Syrians, especially in the border regions. Considering the scale of the influx, there are relatively few news reports pointing to social conflict along Turkish-Syrian lines. European countries on the other hand, have taken in far fewer refugees, but have already gone through several cycles of scandals. Germany for example, having taken in more than a million refugees in 2015, is by far the most generous European country. But accusations of sexual assualt committed by men of “Arab or Noth African background”[8] on New Year’s Eve in 2016 was the latest such case that fuelled outrage in Germany, and continues to be a part of the public discussion there.[9] German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open immigration policy was perhaps the heaviest political blow that she has had to sustain over the years.[10] The public mood is different in Turkey. Though there are reported crimes involving Syrians on a weekly basis, the Turkish public is not nearly as sensitive to the origins of the alleged perpetrators as that in European countries. There are no political movements like the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany — AfD) for example, that base their platforms on anti-immigration policies. The Turkish public sphere’s resistance to scandalizing refugees seems to support the claim that Turkey has an easier time absorbing Muslim refugees due to a shared history.

Walking through ‘Little Syria,’ the first thing one will notice is that the restaurant sings and street chatter is in Arabic.

A second view is the perception of the influx of Syrians as a traditional migration experience, taking into focus the cultural clash that ensues. And much of Syrian settlement in Turkey already resembles the European experience – there is clearly a “ghettoization,” a separate economy of Syrian-only shops and restaurants, as well as very real social differences in terms of language and culture. This is most clear in cities. It is conceivable for example, that a 30 or 40-year old Syrian who lives in “Little Syria” today still will not speak Turkish in 20 years time. Various immigrant communities could also be rubbing shoulders in the years to come. One Turkish person was killed for example, in a fight that erupted between Syrians and Afghans in Istanbul in May 2017.[11]

Discussions on this topic have been relatively muted so far. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government has suggested the idea of giving Syrians citizenship for example, and is finding it to be a very sensitive issue. This is also likely the reason the government instituted very stringent labor laws for Syrians – the thinking being that too many rights for Syrians would cause a popular backlash. Turkey’s resilience to the refugee influx could therefore be a short-term phenomenon. In the long-term, the country could still face some of the same issues Europe is currently dealing with, mainly how to deal with a large, “ghettoized” population.

The most salient difference here could be political. In Europe, the loyalty of the immigrant population is often in question, while in Turkey, Syrians have fled war and feel an allegiance towards the Justice and Development Party (AKP), and President Erdoğan in particular. And though the AKP appears unassailable today, it is by no means sure to govern the country forever. Elections in Turkey no longer pose policy questions, but existential ones. A different election result could therefore lead to a change not merely in how to approach the integration of Syrians, but a change in what that task entails.

The Bonds of War

On the night of 15 July 2016, Syrians from Istanbul to Gaziantep took to the streets to protest the attempted military coup. Over the following days and weeks, journalists would interview jubilant Syrian crowds, who were shouting into microphones about their love for Turkey and President Erdoğan in broken Turkish.[12] These people were not citizens of Turkey, nor were they called on to help, but they felt that their future hinged on the survival of the AKP. Many were afraid that another government might throw them out. “It was a matter of life and death for us,” said one Syrian protester in Istanbul.[13]

When the Syrian civil war started, Turkey made a conscious decision to back the Syrian rebels and help them overthrow the regime of Assad. The struggle has been longer than Ankara suspected, and far more difficult, as it turned out that Ankara did not have the institutional capacity to fuel a successful insurgency. Turkish resources were flowing across the border on a daily basis in the early years, but Turkish agents could not unite the opposition and fashion them into an effective fighting force. Iran on the other hand, brought to bear decades of experience in fighting abroad, with it deploying ground forces such as the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps and successfully propping up forces loyal to the Assad regime. Russian intervention, which came into full force in 2015, made for a decisive loss for Turkey-backed rebels. The war in Syria is far from over, and instability in the country will likely continue in the years and decades to come, but one thing now appears certain: Turkey is on the losing side of a proxy war.

However, a lost war creates bonds as well. The Assad regime has alienated a significant chunk of its own population, while Turkey – despite its faults – accepted millions of refugees. For many of the millions of Syrians now in exile, this is not a trivial matter. Turkey’s moral stance will likely give it great authority over a highly politicized and partly militarized Syrian diaspora.

Chancellor Merkel’s open immigration policy was perhaps the heaviest political blow that she has had to sustain over the years.

In this respect, there is one more concrete gain that the alliance between Syrian rebels and Turkey can hold on to. Under Operation Euphrates Shield, the Turkish Armed Forces liberated territory from Jarablus on the Euphrates as far West as Azzaz, and south including al-Bab from ISIS’ control. Turkish companies are now rebuilding entire towns in territories under Opearation Euphrates Shield and ministries are providing public services, ranging from first aid to education. Newly minted police officers are patrolling the streets wearing Turkish hand-me-downs. Though Turkey’s war fighting capabilities were limited, its ability to build and sustain a large civilian environment is unparalleled in the region.

Operation Euphrates Shield echoes the Cyprus Peace Operation of 1974, when Turkey intervened on the island to protect its Turkish population. The result was a statelet almost entirely dependent on Turkish support for its existence, thereby giving Turkey leverage over what happened on the island.[14] If Turkey manages to hold on to Euphrates Shield territory, it could become a highly strategic position for Ankara’s reach into Syria. The nearly one million people living in the territory would in effect be part of the larger Syrian population within Turkey.[15] Given their experiences, these people could also be a source of politically motivated talent in future Turkish operations in the region.

When Turkey waded into the Syrian civil war in 2011, it showed little skill in navigating the political and tactical space in the country. This could change in the future. Turkey now has organic links in the region. If it manages to capitalize on these, it could become a far more determinant actor in the political dynamics of the region.

The Bonds of Commerce

Turkey and Syria have had a fraught history. The district of Hatay was contested between the countries in the 1920s, only officially becoming part of Turkey in 1939. In the 1980s, Syria began to harbor Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants, which led to periodic friction between the countries. In 1998, Turkey even threatened to invade Syria. Trade was basically non-existent during this time. But by the late 2000s, relations began to look up. Syria’s stance had softened after the death of Hafez al-Assad, and Turkey’s new government was more eager to resolve long-standing disputes such as on water rights and the Kurdish issue. The AKP government made several trips to the country, lifted visa restrictions, conducted joint military exercises, and boosted trade. Turkey’s exports to Syria took off starting in 2008, peaking at 1.8 billion dollars in 2010. Much of this trade was made up of intermediate goods such as electronics and motor vehicles built or assembled in Turkey’s southern provinces, most notably Gaziantep. This was an important step for the regional development of Turkey. For the first time, a poor Anatolian region was exporting without heavily relying on the Western Marmara region, which is where Turkish industry has traditionally been based.

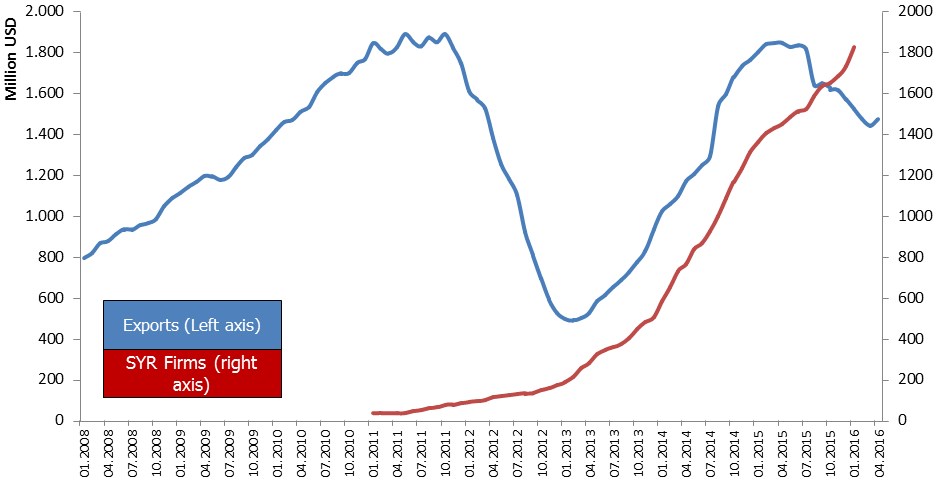

When the civil war started however, trade took a nosedive. Soon, though, a new economic dynamic emerged. In late 2013, Turkish exports into Syria rose again (see figure three). The composition of goods exported to Syria now differed – basic goods included wheat, flour, sugar, and cement. By this time, Turkey was deeply involved in the Syrian conflict across its border, and was supplying its proxies with whatever they needed under wartime conditions. This new dynamic however, appears to have been conditional on Turkey being involved in the Syrian war. In 2015, Turkey-based rebels began to lose ground to Assad regime’s forces backed by heavy Russian bombardment, and Turkey’s exports began to wane.

Figure 3: Turkey’s exports to Syria and number of companies established or partnered with Syrian businessmen

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute & TOBB, TEPAV calculations

Although Turkish economic involvement in northern Syria could remain limited in the near future, the seeds of a Turkish-Syrian economy have been sown. Parallel to the uptick in Turkish wartime exports was an increase in Syrian-owned businesses in Turkey. Between January 2011 and April 2017, the number of companies established in Turkey with Syrian capital stood at 5,797, with the total seed capital of these companies estimated to stand at 1.9 billion Turkish Liras.[16] Southeastern and western metropolitan centers in Turkey in particular have increasingly been becoming hubs for Syrian entrepreneurs. 2,870 new businesses with Syrian capital were registered in Istanbul, the country’s economic center. This is to be expected, but the relative importance of Syrian entrepreneurship is much higher in southeast Turkey, where one third of Syrians reside.

One thing now appears certain: Turkey is on the losing side of a proxy war.

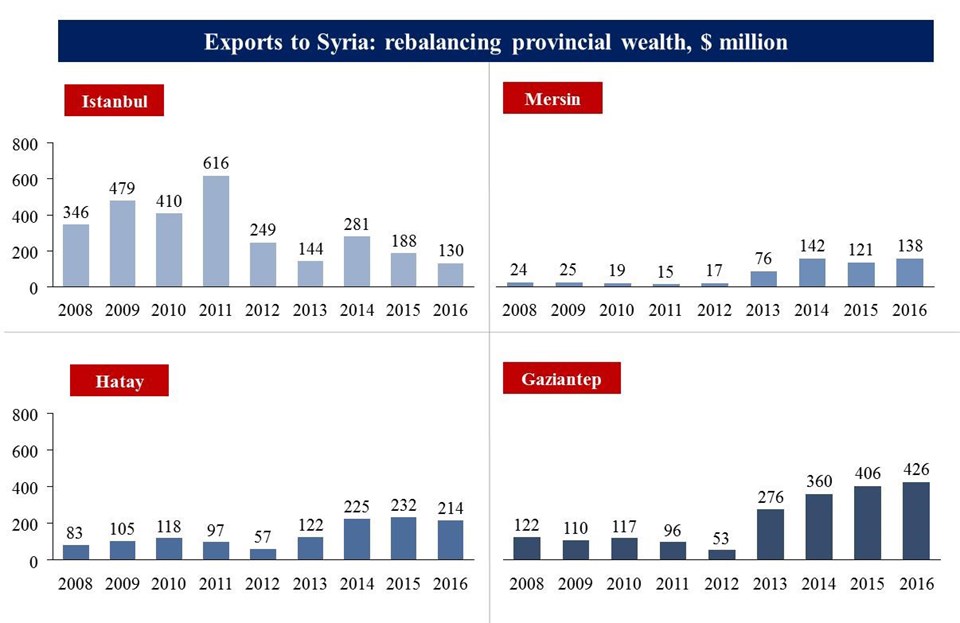

A new Turkish-Arab economic space is taking shape that is relatively independent of Turkey’s traditional industrial hub (see figure four). Before the war, Istanbul was the export leader to Syria, with 616 million dollars in 2011. Now, it is Gaziantep with 426 million dollars in 2016. Hatay exports 214 million dollars. Part of this could be due to Syrian businessmen who resettle in these provinces and bring with them the know-how and familiarity of their home market. This allows for a more integrated economy across the border. There is currently no data to establish this causal link, but anecdotal evidence gathered throughout the region suggests that this might well be the case.

Figure 4: Exports of Turkey’s provinces to Syria, US dollars (million)

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute, TEPAV calculations

What This Means for Europe

Throughout the history of the Republic, Turkey has been the epitome of a nation state, strong in its self-perception as a homogeneous entity. This is gradually changing. For the first time since the fall of the Ottoman Empire, there is again a vibrant cultural, economic, and political Turkish-Arab space. But unlike at the time of the Ottoman Empire, it is not Turks traveling to Arab centers, but Arabs who are resettling into Turkey. All this means that the border between the Arab world and Turkey, and by extension, Europe, is becoming more blurry.

Europe could choose to be part of this new space. There are 720,000 Syrian refugees across Europe, mostly in Germany. Decades from now, these people are going to be part of a wider network of the Syrian diaspora. Already, there are families scattered across Turkish and European cities, keeping in touch through Skype conversations and even getting together for small reunions. Over time, these connections could translate into the fields of business and governance. European countries are often more concerned about integrating new arrivals than in maintaining their connections to their home countries. But there could be benefits to being a hub for the Syrian diaspora in the decades to come.

At the same time, mainstream political parties in Europe face the threat of a far-right resurgence fuelled by anti-refugee sentiments. This is why, in order to control the flow of migrants through its borders, European states need to do more to make Turkey a better destination country for migrants. The Turkish experience shows us that there are many mechanisms in place to help less developed countries such as Lebanon or Jordan to cope with refugees, but relatively little to a help middle-income country such as Turkey. European programs would do well to focus on working with Turkish institutions to strengthen their integration capabilities. This includes issues such as access to finance, labor market integration, social programs, and pathways to citizenship. The more refined the Turkish state’s mechanisms are in accommodating Syrian refugees, the better for Europe.

[1] “Suriyeli Mülteciler Hatay’da” [“Syrian refugees in Hatay”] T24, 30 April 2011, http://t24.com.tr/haber/suriyeli-multeciler-hatayda--hatay-aa,142211

[2] Mehmet Balcilar and Jeffery B Nugent, “The Migration of Fear: An Analysis of Migration Choices of Syrian Refugees,” Researchgate, December 2016, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311924314_The_Migration_of_Fear_An_Analysis_of_Migration_Choices_of_Syrian_Refugees

[3] Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM), Accessed 25 May 2017, http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik6/gecici-koruma_363_378_4713_icerik

[4] “Syrian Nationals Benefiting from Temporary Protection in Turkey,” Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM), http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik3/syrian-nationals-benefiting-from-temporary-protection-in-turkey_917_1064_4773

[5] “Geçici Koruma Sağlanan Yabancıların Çalışma İzinlerine Dair Uygulama Rehberi” [“Application Guide for Foreigners Under Temporary Protection,”] Ministry of Labor and Social Security, http://www.calismaizni.gov.tr/media/1035/gkkuygulama.pdf

[6] Patrick Kingsley, “Fewer than 0.1% of Syrians in Turkey in line for work permits,” The Guardian, 11 April 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/11/fewer-than-01-of-syrians-in-turkey-in-line-for-work-permits

[7] Sedat Cenikli, “Küçük Halep’te yıkım başladı” [“The demolition starts in Little Aleppo”] Hurriyet, 2 August 2015, http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/kucuk-halepte-yikim-basladi-29677925

[8] “String of New Year’s Eve sexual assaults outrages Colone,” DW, 1 January 2016, http://www.dw.com/en/string-of-new-years-eve-sexual-assaults-outrages-cologne/a-18958334

[9] “Angst vor Flüchtlingen: Ablehnen, asugrenzen, abschieben?” [“Fear of Refugees: Reject, deport, keep away?”] Das Erste, 7 December 2016, http://www.daserste.de/unterhaltung/talk/maischberger/sendung/angst-vor-fluechtlingen-ablehnen-ausgrenzen-abschieben-100.html

[10] Erik Kirschbaum, “Arrest of refugee in rape and slaying in Germany threatens Merkel’s immigration policy,” Los Angeles Times, 5 December 2016, http://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-germany-refugee-murder-20161205-story.html

[11] “İstanbul Sultangazi’de Afgan ve Suriyeli Gruplar Kavga Etti: 1 Ölü” [“Afghan and Syrian Groups Fought in Istanbul Sultangazi: 1 Dead”] Karar, 15 May 2017, http://www.karar.com/guncel-haberler/istanbul-sultangazide-afgan-ve-suriyeli-gruplar-kavga-etti-1-olu-481378

[12] “Suriyeliler Çıldırmış olmalı” [“The Syrians must have gone crazy”] YouTube, 25 May 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ip2UpjMvJoE

[13] Erika Solomon, “Syrian refugee support for Erdogan repays past favours,” Financial Times, 20 July 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/d3435a96-4e76-11e6-8172-e39ecd3b86fc

[14] “Fırat kalkanı harektı sonrası bölgede hayat normale döndü” [“Life went back to normal in the region after the Operation Euphrats Shield”] TR Diplomacy, 20 May 2017, https://twitter.com/TRDiplomacy/status/867698061665067008

[15] “Yeni Şafak: Fırat Kalkanıyla temizlenen bölgelerdeki nüfus yaklaşık 1 milyon” [“Yeni Şafak: The Area Cleared by Euphrates Shield has a Population of About 1 Million”] T24, 19 May 2017, http://t24.com.tr/haber/yeni-safak-firat-kalkaniyla-temizlenen-bolgelerdeki-nufus-yaklasik-1-milyon,404987

[16] Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey (TOBB), TEPAV private access