The threatening winds of change have forced the global architecture of the last seven decades to create new ground rules necessary to regulate new issues of services, e-commerce, and cross-border data flows. A huge task by itself nowadays, the pursuit to create new rules that will provide solutions was compounded by a series of anti-globalist populist policies adopted by the system’s major stakeholders. The last meaningful multilateral agreement adopted was over 25 years ago at the Uruguay Round in 1994. Since then, there have been some minor agreements at the multilateral level, such as the agreement on Trade Facilitation, but these fell short of providing solutions to pressing global trade issues. Additionally, the sheer momentum of technological advances brought about a sense of urgency to the process. The need to add new chapters to the existing rule book of trade could have been depicted as business as usual for the World Trade Organization (WTO) had the organization kept its central role and relevance in matters of global trade.

Through the Bretton Woods system, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB), and World Trade Organization (WTO)—formerly known as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)—accomplished their functions and ensured relative stability in global finance and trade for seven decades. This liberal economic order overcame difficulties by forming coalitions led by the US and European countries. At the turn of the millennium, most countries embraced and lauded globalization—the Russian Federation and China became major stakeholders in the system. In time, inadequacies of the system surfaced and were tackled with a multilateral approach.

Following the 2008 crisis, global cooperation began to break down, and as the emerging economies’ shares in the global economy increased, these countries were hailed as the new saviors of a broken system. On the other hand, particularly in advanced economies, the frustrations of certain segments of the society on the widening income gap—a byproduct of globalization—became more pronounced. The grievance surrounding inequality became one of the most polarizing issues in democratic industrialized countries.

The rule-making processes of the global trading system initially began with efforts aimed at “multilateralism,” which in seven decades became a push for “plurilateralism.” The plurilateral aspirations resulted in major undertakings such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with 12 member countries; Transatlantic Trade and Investment (TTIP) with the EU-28 as members; The Trade in Services Agreement (TISA) with 23 member countries; and The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with 16 member countries. Unfortunately, these attempts were not successful in providing new chapters to the rules-based trade system; thus, multi-national trade agreements were once again replaced by raw “bilateralism.” Subsequently, the global system entered an era of uncertainty.

Furthermore, recent US trade policy changes have imposed undue strain on the rules-based system. The international liberal order—generally viewed as the main mechanism that improved the living standards in nations, reduced extreme poverty, and lowered trade tensions—become a divisive issue. Populist politicians stoked anti-globalist views among their electorate by extolling protectionism and channeling societal frustration with the current system into a nationalist political platform. The waves of mass immigration into Europe caused by the unrest in Middle-East, North Africa, and Afghanistan only exacerbated such sentiments.

Challenges Facing the Rules-Based System

For the past few decades, major companies have been diverting their production capabilities to developing countries where labor costs are lower. Global supply chains are being utilized by companies to make purchases of goods or parts and services from other countries for profit maximization. In the words of Richard Baldwin, “with many products made everywhere trade has been, in effect, denationalized.”[1] In other words, a worker in Mexico working in the Ford factory replaces the American worker in Detroit financed by the US banks and know-how provided by the Ford Motor Company. Also, “inequality” fed by anti-global sentiment has already made a gradual encroachment on blue-collar workers in advanced economies.

Deviating from traditional American trade policy, President Trump is more focused on negotiations for one-on-one trade agreements rather than plurilateral or multilateral deals.

This anti-globalist and nationalist attitude has resulted in a populist backlash as was seen in the Brexit vote in the UK in June 2016, the election of Donald Trump in the US, and the electoral victories of populist leaders across Europe. Professor Henrik Enderlein portrays the connection between structurally conservative leftist and nation-state romantics as an unholy alliance. The emerging new structure does not fit the clean left and right model of the past. Those skeptical of an open society in both camps are connected by the fear of being left behind and find common ground in their opposition to globalization.[2] The nationalist/populist upheaval and the causes that have fueled it in the UK should be the subject of a separate article. That being said, the scope of this article will focus on US President Donald Trump’s trade policies and their implications for the foundations of the existing system.

President Trump gave the impression that he would embark on a systemic denial of the rules-based trading system by questioning the authority of the WTO. However, President Trump’s opening salvos clearly showed that he intends to exploit the exceptions to the rules inherent in the system that can only be applied in rare cases. The invoking of “safeguard” and the “national security” articles of the WTO agreements to impose additional tariffs to cars and washing machines imported from countries like Canada and NATO allies do not comply with the rationale of why these rules were formulated in the first place.

Most of the rules adopted by the WTO target unfair practices and offer remedies to offset the unjust practices of trading parties. Of course, some countries do resort to plain protectionism and the weaponization of trade, which upsets the rules-based global trade system. For instance, the protectionist policies championed by President Trump are realized only through the coercive use of the innocent and otherwise benign instruments of the trading system. The way the US interacts with other countries in trade and economic issues seems now to have entered a new phase. There is a risk of trade becoming predominately political, rather than economic.[3]

Trump’s Trade Salvo

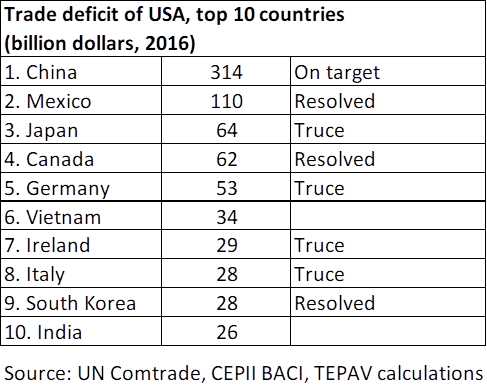

After making trade agreements a major campaign issue and focusing on the negative impact of free trade on American blue-collar workers, President Trump did not lose any time in initiating policies that were against the multilateral rules-based trading system. One of President Trump’s first executive actions was to withdraw the US from the TPP, a hallmark of the Obama administration. Deviating from traditional American trade policy, President Trump is more focused on negotiations for one-on-one trade agreements rather than plurilateral or multilateral deals. Trump took action against countries that the US has a major trade deficit in.

- The renegotiation and renaming of the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to the US Mexico Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA), which was signed on 30 November 2018. The new version of the agreement solidified additional conditions for automakers, labor and environmental standards, intellectual property protection, and digital trade. The provision regarding non-market economy trade partners of the three countries plainly targets China.

- The European Union and the US struck a truce to defuse tensions on 26 July 2018 between the European Commission President Juncker and President Trump. Both sides agreed to put a hold on any new tariffs and proclaimed a new phase in transatlantic relations. The talks targeted the reduction of tariffs and trade barriers related to all industrial goods, excluding cars. Six months later, the prepared position papers of both sides clearly showed the absence of a common approach. The EU decision[4] proposes a limited deal including regulatory alignment and provisions on motor vehicles. On the other hand, the objectives put forward by the US Trade Representative[5] in January 2019 contain agricultural products and public procurement. The chapter on agriculture is considered to be the most controversial issue due to the different standards of both sides on food safety as the EU rejects genetically modified food from the US. For both the US and EU, finding common ground to kick-start realistic negotiations seems to be difficult.

- During the UN Summit Meetings in New York on 26 September 2018, President Trump and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe decided to enter into negotiations for a US-Japan Trade Agreement. Both sides decided to refrain from taking measures that will go against the spirit of the decision during the process of negotiations and reiterated their commitment to strengthening their cooperation in non-market economies. Thus, another truce was achieved.

- President Trump claimed that the Free Trade Agreement between Korea and the US which entered into force on 15 March 2012 was unacceptable and needed to be scrapped or reworked. The issue with Korea was resolved following a long series of negotiations between the US Trade Representative and Trade Minister of Korea, where an agreement was reached to amend certain articles on 24 September 2018.

- It is odd that Vietnam and India have never been a focus in trade discussions in Washington even though the US trade deficit with both countries totals 34 billion dollars and 26 billion dollars, respectively.

As the Trump Administration’s trade strategy unfolds, a coherent approach is starting to surface. President Trump has placed pressure on countries with which the US has a major trade deficit. He lambastes them publicly, places tariffs on steel and aluminum products, threatens to increase tariffs on automobiles, bullies them that he is ready to double the tariffs and calls himself a “tariff man.” Even the US’ traditional allies are treated the same way. President Trump has employed coercive methods banking on the economic and sometimes even the military might of the US to extract concessions on trade. Now that the truce with the EU and Japan and the revised deal on NAFTA and KORUS are in place, President Trump will focus on his ultimate goal: leveling the playing field with China.

Deviating from traditional American trade policy, President Trump is more focused on negotiations for one-on-one trade agreements rather than plurilateral or multilateral deals.

Targeting China

Current trade tensions between the US and China do not only stem from the huge trade deficit but also from the possibility of a Chinese challenge for global leadership. In 2017, the US imported 505 billion dollars’ worth of goods from China while exporting a mere 130 billion dollars’ worth, therefore, resulting in a trade deficit of 375 billion dollars.[6] President Trump imposed taxes in multiple installments on the goods imported from China to the US and threatened to increase them from 10 percent to 25. The G20 summit meeting at Buenos Aires provided an opportunity for President Trump and Chinese President Xi to meet. During the meeting, both parties agreed to put the additional tariff hikes on hold until 1 March 2019 and continue with negotiations for another three months to find an amicable solution for their reciprocal grievances. The early rounds of negotiations at technical levels already took place in Beijing and Washington.

Beijing seems to be receptive to US requests to increase its importation of farm products and energy, along with some expectation to make modest improvements and reforms in its industrial policies. However, other US demands constitute major difficulties: structural reforms in Chinese industrial policies through the elimination of subsidies for state-owned companies specialized in telecommunications, banking, and insurance; reforms aimed at reducing the vulnerability of US companies to the forced transfer of technology; and the eradication of discrimination against foreign companies. The US further seeks for a verification process to be agreed upon in the negotiations. China launched “Made in China 2025,” a program which aims to make China a world leader in the semiconductor industry and G5 technology, and allocates vast sums of financing to the program. However, Chinese plans of leading G5 technology were met with suspicion by the US, as Mike Rogers, the chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, stated that federal prosecutors will charge “the Chinese technology company Huawei with crimes including bank fraud, sanctions violations and theft of trade secrets.” Rogers claimed that China had used companies such as Huawei as an extension of its intelligence network to advance Chinese interests as 5G technology will “revolutionize the way we use technology, and China wants dominance from the start.”[7]

The ratio of China’s savings to global savings is 26 percent, whereas the EU and the US’ combined savings ratio makes over 35 percent. It is clear that China could easily earmark large sums of capital to prioritized fields. However, China denies forced technology transfer accusations and reiterates the idea of “competitive neutrality” in which the state would not favor state-owned firms over privately owned ones.

| |

Contribution to global annual gross savings (%)

|

|

Year

|

EU plus USA

|

China

|

|

2010

|

35.17

|

18.97

|

|

2011

|

33.15

|

20.10

|

|

2012

|

32.02

|

21.62

|

|

2013

|

33.33

|

23.41

|

|

2014

|

34.38

|

24.49

|

|

2015

|

35.62

|

26.62

|

|

2016

|

35.78

|

26.24

|

Source: World Bank – World Development Indicators

Against this backdrop, Chinese Vice Premier Liu He had high-level talks, including one with President Trump at the end of January 2019. The meetings represented the first cabinet-level negotiations. However, the US Administration decided to wage criminal charges against Huawei Communications and its chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou just two days prior to the meeting in Washington. The chance of reaching a deal between the two biggest economies of the world, therefore, seemed dim.

After the meeting with Liu He on 31 January 2019, President Trump gave confusing signals. US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer asserted that substantive progress was made during the talks, which focused on trade, structural issues, and enforcement. Although President Trump initially accepted the Chinese proposal to meet with President Xi in Hainan in late February, he added that he might extend the talks further than the deadline to reach a comprehensive deal. However, later that day, he declared that an extension would not be necessary.

The Trump Administration is using trade as a tool of coercion to accomplish foreign and security policy goals.

Lighthizer and the US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin traveled to China in early February to continue with the negotiations. Upon their return from China, the US team headed by Lighthizer and Mnuchin briefed President Trump on the progress achieved. President Trump’s reaction was quite positive, sanctioning the outcome with a tweet: “Big progress being made on so many different fronts.” This time, China will dispatch a high-level team at the cabinet level in mid-February to resume the negotiations in Washington. However, people who were briefed on the negotiations said significant sticking points remain.[8] At this juncture, the Trump Administration may be willing to extend the deadline to increase the tariffs on Chinese imports to 25 percent, and is currently pushing hard to reach a deal with China without resorting to harsher actions.

Conclusion

The methods that the Trump Administration resort to go well beyond conventional trade measures. In other words, trade is being used as a tool of coercion to accomplish foreign and security policy goals. At this point, is it safe to assume that the weaponization of trade will prevail as a way for other major stakeholders to follow?

The US aims to find solutions to structural issues in its bilateral relations with China through a trade deal. The meeting of the two presidents will be highly critical since both sides will be under pressure to come up with either a solution or a deferral for future talks. As the date of the meeting approaches, the expectation for a positive outcome from the public will grow. China is an integral part of the global trade system and cooperation with it is vital for the sustainability of global interdependence today.

Trade wars or extended tensions among major stakeholders have been disruptive to the world economy in the past and the extensive use of trade as an instrument of coercion has the potential to be highly destructive in the days to come. The very structure of multilateral free trade that took nearly seven decades to develop will be negatively affected, and peacefully dealing with trade issues through the WTO panel system will be under great strain. Until now, more than 500 trade disputes have been dealt within the WTO system. If the centrality of the WTO in dispute settlement is undermined, trade issues will be dealt with through coercion among states which in turn will generate more uncertainty in the international arena. The public reaction to uncertainty could stoke populist forces around the world and contribute to rising protectionism.

[1] Richard Baldwin, The Great Convergence, Information Technology and the New Globalization (Belknap Press, 2016).

[2] “A Turning Point for Globalization: Inequality, Market Chaos and Angry Voters,” Spiegel, 17 November 2016, http//www.spiegel.de/international/world/globalization-failures-have-world-at-a-turning-point-a-1121515.html

[3] Rebecca Harding and James Harding, The Weaponization of Trade (London Publishing Partnership, 2017), p. 3.

[4] European Commission, “Recommendation for a Council Decision authorising the opening of negotiations of an agreement with the United States of America on the elimination of tariffs for industrial goods,” 18 January 2019, http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2019/EN/COM-2019-16-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF

[5] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “Summary of Specific Negotiating Objectives for the Initiation of United States-European Union Negotiations,” January 2019, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/01.11.2019_Summary_of_U.S.-EU_Negotiating_Objectives.pdf

[6] United States Census Bureau, “2018: US trade in goods with China,” https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

[7] Mike Rogers, “The 5G Promise and the Huawei Threat,” Wall Street Journal, 28 January 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-5g-promise-and-the-huawei-threat-11548722842

[8] J. M. Schilesinger, “As China Talks resume Trump Seeks a Win on Trade,” Wall Street Journal, 18 February 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/as-china-talks-resume-trump-seeks-a-win-on-trade-11550537816