After the end of the Cold War, the debates on the future of minority groups in new regimes established in Eastern European countries have become intensive. After the accession of more of these countries to international bodies, including the European Union, the strategies and policies carried on towards minority groups started to be debated in a greater context than just a restricted analysis based on domestic policies of any given country. This article aims to analyze the status of Russian and Hungarian ethnic minorities living in Latvia and Romania, respectively, and point out the key differences and similarities observed in their ethnopolitical rights. The puzzle question we need to answer is “How could Hungarians in Romania achieve a greater political and cultural integration despite their relatively low numbers, whereas Russians in Latvia are still considered as a “fifth column,” and more isolationist policies are applied toward them?”.

Latvia: The Russian Question

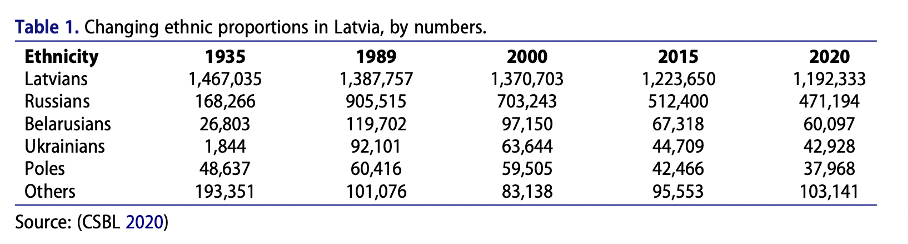

Latvia was a part of the Russian Empire for centuries. Still, a great majority of Russian migrants had settled in-country during the USSR period due to the desire of the Communist Party to prevent a possible separative attempt as it could happen after the fall of Tsarist rule[1]. A recent study illustrated that the ethnic composition of Latvian lands changed significantly in favor of Russians, at the expense of Latvians, between 1935 to 1989:[2]

These numbers facilitate our understanding of the Latvian approach toward the so-called “Russian Question.” Because of such significance that migratory dynamics had in transforming Latvia's demographic portrait during the Soviet era, the issue of migration became a contentious issue in the 1990s. Under perestroika, the migration issue, as well as the language issue, were among the most common debate topics from the start of the national rebirth.[3] Especially the Latvian nationalists were critical of the migration issue, and the demands for the establishment of Latvian identity at the expense of Russian-led ethnic minorities of Soviet legacy to secure “the Latvian control of Latvian soil” became a crucial part of Latvian nation-building.[4] Considering the 24.7 percent of the share of the Russian minority in the overall population, it is not hard to understand this Latvian approach.

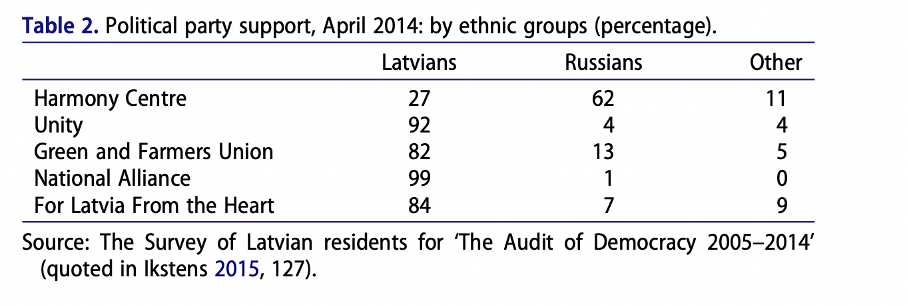

Studies show us that the Russian minority in Latvia lacks a centralized political agenda and a leadership institution. In most cases, they vote for more central parties instead of political parties with a clear minority foundation.[5] For instance, they vote at high levels for central political parties such as Harmony, as can be seen from a data coming from the 2014 elections:[6]

Logically, the Latvian – Russian relations significantly impact the Latvian stance towards its Russian minority. Latvians never let their guard down against their “old patronage”. Even today, the Latvian leadership perceives ethnic Russians as potential targets of Kremlin propaganda to disregard the Latvian stability and political independence, primarily through the utilization of Russian language schools that even today a significant number of such families continue to send their children for education.[7] That is why it is common in Latvian politics to consider that the Russian minority is nothing more than “the fifth column within their borders.”[8]

Hungarians in Romania: More Regionally Concentrated & Independent from Bilateral Ties

The share of Hungarians in the Romanian demographics constitutes even a smaller share compared to the Russian minority in Latvia. Relevant figures suggest that approximately a 6 percent Romanian population belongs to this Hungarian minority, who mostly lives in borderline areas next to Hungary, known as Transilvania.[9] Interestingly, the Hungarians in Romania differ from Russians in Latvia in a vital aspect – they are more concentrated in a specific borderline region. In contrast, the Russian minority in Latvia lives in almost every urban area with a considerable number.[10]

Romanians’ providing more extensive rights for the use of the Hungarian language in different aspects of life, including judicial matters, provides a good understanding of the better position they have compared to the Russian minority in Latvia.[11] In fact, minority languages are now widely utilized at all levels of education. A crucial factor in determining the contemporary situation of ethnic minorities in Romania is the extended ability to utilize minority languages.[12] Of course, here, we can argue for a strong influence of external actors, including the EU. Therefore, it is possible to build a framework that focuses on the positive impact of external actors and domestic compromises.

Hungarians in Romania are very active in political life. Although they only constitute 6 percent of the total population, their political participation reflects itself through the famous political party known as The Democratic Alliance of Hungarians. Party even acts like a kingmaker and has joined eight of twenty-one governments that have been established in-country since the transition to democracy.

Variables, Methodology, and Conclusions

This puzzle examined the conditions of both minority groups within their respective countries by analyzing fundamental variables. Those independent variables are "Composition of Minority’s Population Distribution", "Their Political Participation", and finally, "the Nature of Relations Between Settled and Home Countries”.

Composition of Minority’s Population Distribution was an independent variable that asked whether the minority group lives predominantly in a region instead of living homogenously. Nationwide statistics can measure it. The hypothesis here was to observe a more proactive stance to isolate a minority group concentrated on a specific region; however, the findings suggest otherwise. Therefore, Romania considers Hungarians not a threat to their national integrity (which can be supported by the relatively low population share) compared to Latvians, who have a Russian minority living almost in every urban center.

Political Participation of Minority Groups was a variable aiming to understand whether the respective minority group tries to establish a separate ethnic-focused political party to access more political rights or supports more central political parties. Our findings suggest that Hungarians in Romania are more involved in political decision-making, as they have a political party focusing on their rights instead of nationwide central politics. This is what the Russian minority in Latvia lacks – a charismatic political leadership and a strong ethnic political party that can negotiate for further rights. Although they have several parties that we can consider an ethnic party, they have no relevant political support.

Lastly, the dynamics of bilateral relations between settled and home countries of those minority groups are very determinantal. It is possible to show that Latvian consideration of Russia as an aggressor country that threatens Latvian independence affects the political and cultural rights of the Russian minority living in Latvia. On the other hand, relatively better relations between Romania and Hungary can be another reason why Romanians treat the Hungarian minority easier. These all played a crucial role in making Hungarians’ position in Romania better than Russians in Latvia.

[1] Here, an additional reading can be carried out on the interesting work of Francine Hirsch, who explains the political climate before and during the Soviet invasion of Baltic countries. Furthermore, her discussion on the passport system and the Soviet approach to borderline regions with enemy regimes has a wide range of implications for the Latvian story. See Francine Hirsch, Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of Soviet Union (Cornell University Press, 2005).

[2] A. Antane and B. Tsilevich, “Nation-building and ethnic integration in Latvia.” Nation-Building and Ethnic Integration in Post-Soviet Societies(2019): p. 63-152.

[3] A. Antane and B. Tsilevich, (2019): p. 70.

[4] A. Antane and B. Tsilevich, (2019): p. 81.

[5] A. Antane and B. Tsilevich, (2019), p. 105.

[6] Rasma Karklins, "Integration in Latvia: A Success Story?" Journal of Baltic Studies, Vol. 52, No. 3 (2021): p. 455-470.

[7] Ma¯ris Cepuri¯tis and Austris Keisˆs. “Hostile Narratives and Their Impact: The Case of Latvia,” in Russia’s Footprint in the Nordic-Baltic Information Environment, Report 2019/2020, Vol. 2 (2020).

[8] Ma¯ris Cepuri¯tis and Austris Keisˆs, (2020), p. 145.

[10] A. Antane and B. Tsilevich, (2019), p. 145.

[11] Kiril Kolev, “Weak Pluralism and Shallow Democracy: The Rise of Identity Politics in Bulgaria and Romania,” East European Politics, Vol. 36, No. 2 (2020): p. 188-205.

[12] Dragoş Dragoman, “Language Planning and the Issue of Hungarian Minority Language in Post-Communist Romania: from Exclusion to Reasonable Compromises,” Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, Vol. 18, No 1 (2018): 121-140.